About two months ago I wrote a piece here on rules-lite superhero games. In the piece I talked about a bunch of games, and at the end I made a list of the games that I found most essential.

I recommend reading these Revisited articles first and then circling back to my original piece, because everything I say here supersedes my opinions from the original piece. The important thing to note is that I didn’t actually read the rulebooks for almost all of the games I discussed; I read forums posts and reviews, listened to podcasts, read product descriptions, and studied other sources to get some kind of rough idea about each game.

In this four part series I’m going to go deeper and take a closer look at the handful of games that I said I most wanted to play last time, which is to say I’m going to read the rulebooks and make further observations about the games. I’m also going to look at a small handful of games that I didn’t mention last time, and look at the rulebooks for most of those as well.

I would also like to say something about my prior piece; I was a little intense about the “Parker luck” stuff. If a superhero game is basically an optimized system for moving through traditional superhero adventures, that’s totally fine. I mostly stand by what I said; some games are so rudimentary and lacking in flavor that they really don’t seem compelling to use. Even non-narrative superhero games can have genre-emulating elements, and so games without any of that stuff don’t really have an excuse.

But, for whatever reason, when it comes to superhero stuff I want a mixture of players having a lot of narrative control as well as GMs being able to provide complications and challenges. And out-of-costume stuff will always be a huge plus for me, even if I’m more receptive now to games that focus almost exclusively on what superheroes are up to when they’re with their teams only.

While putting the finishing touches on my original piece, I managed to find a used copy of Truth & Justice on eBay, which apparently had been given to the seller, a playtester, by Chad Underkoffler himself. Now that I own a physical copy of a superhero RPG, the bar has been raised a lot higher for any other games I might purchase physically; the question is now “Does this other game seem so intriguing that I’m willing to give up the shelf space for it, when I already own a superhero game?”. This will become especially relevant when I share my final conclusions and say which games I truly wish I owned physically.

Because of the amount of reading I’m going to be doing for this piece, I have divided it into four parts. The stuff about new games and stuff about games I’ve already mentioned will be split evenly across each part.

Games I Didn’t Talk About Last Time

Smallville

I did mention Smallville in passing while talking about Marvel Heroic, but did not discuss it in any kind of detail. I think Smallville does some important stuff, however, so I’m going to take a deeper dive.

I saw a great video about how the Cortex Prime system works. The basic mechanics are simple enough, but the highly modular toolkit nature of the larger system makes it seem extremely daunting to actually use. I can only speak for myself, but there would be way too much second-guessing involved in assessing all the possible options as a Cortex Prime1 GM.

I mention this because there’s a real value in games like Marvel Heroic and Smallville that present GMs with a ruleset pre-optimized for a specific purpose. FATE has a game for everything because it has an open CC-BY license. Cortex doesn’t; the creator of Cortex Prime has said there are discussions relating to a commercial Cortex license, but nothing has materialized yet. Obviously if someone doesn’t want to make their system open they don’t have to2, but systems that are open are systems that are allowed to grow. That was a slight diversion, but I just needed to say that.

Anyways, I should make it very clear that Smallville is first and foremost a CW superhero-soap simulator and not really a straight superhero game. Smallville is a game where, mechanically, non-powered characters like Lois Lane are equally as effective as characters like Clark Kent. That might sound interesting and desirable to you, or that might make you completely disinterested. I love the soap parts of comics, really more so than the fighting, and so Smallville has always interested me. I should quickly mention that Smallville is explicitly designed to both emulate the show’s setting and act as a more setting-agnostic superhero soap system.

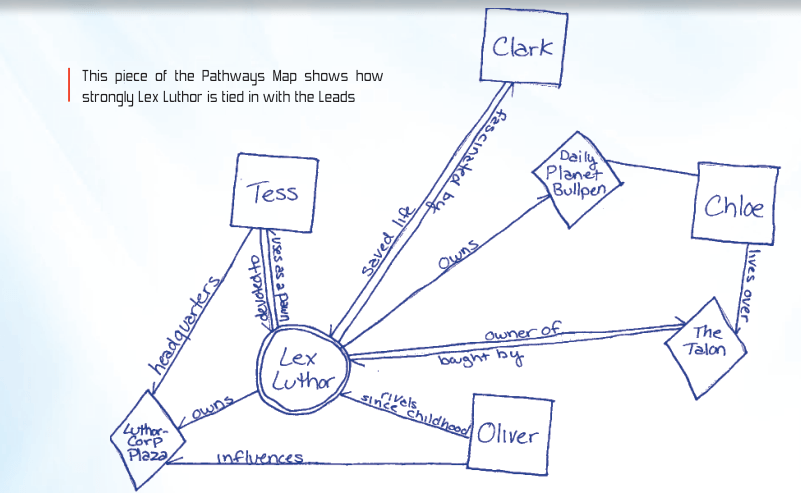

Marvel Heroic uses what can broadly be considered the same system, but Smallville was the only Cortex Plus game to use the Cortex Plus Drama rules variant. Possibly the most famous thing about Smallville is its character creation / worldbuilding tool, known as the Pathways System3. The first session of a Smallville campaign involves players collaboratively creating a giant map of relationships. Not only are player characters put onto this map, but also supporting characters and locations.

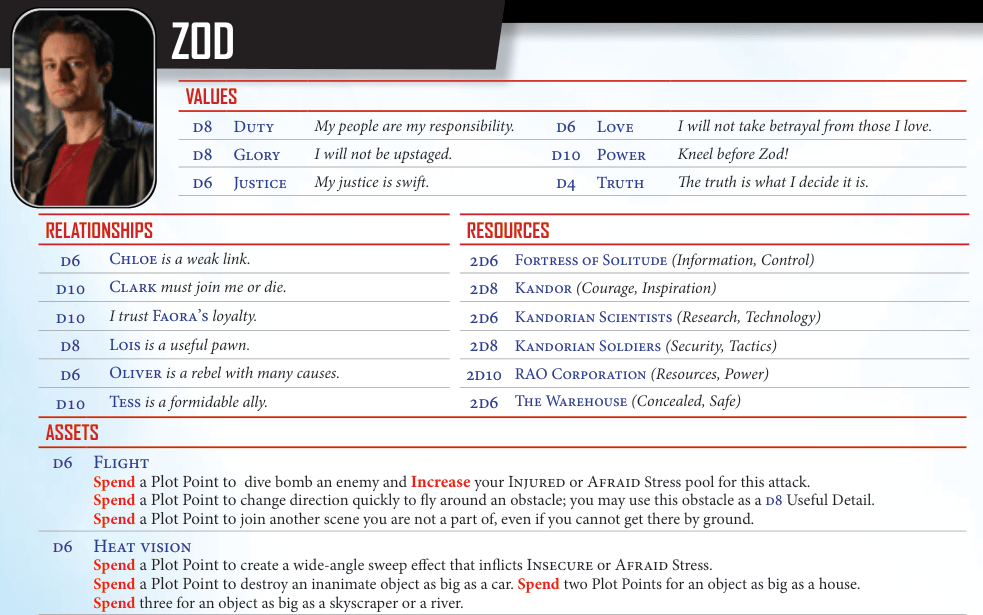

During session zero players also develop their values, relationships, resources, and assets. Smallville characters don’t have normal stats; they have contextual phrases that have a die value. These are kind of like FATE Aspects; you can get points when they disadvantage you, and they’re highly narrative on a gameplay level. This makes sense, because a lot of the people who worked on this era of Cortex Plus games have Evil Hat connections.

You might be wondering how the non-powered characters are able to compete with the superpowered ones in this game. The answer is simple; the game does not emulate team superhero stuff. Gameplay is meant to emulate Clark Kent’s will-they-or-won’t-they relationships, Lois Lane’s investigative reporting, Lex Luthor’s business dealings, etc. Superpowers obviously have uses, but Clark Kent’s heat vision doesn’t have much utility if he’s trying to convince Lois Lane to do something4.

Gameplay in Smallville has some interesting wrinkles. The GM sets each scene, which is quite normal. But unlike in most games, it’s expected that only two or three players will usually be present in a given scene, rather than the entire group. Continuing with this dedication to emulating superhero soap storytelling, Smallville also includes a lot of useful notes on how to run the game. This includes advice on how to center different characters in different episodes, how to know when to end scenes, and how to find points of conflict between characters.

The dice rolling in Smallville is unusual. Like I said before, characters have short phrases describing their feelings about things, which have their own die values. When a character is arguing with another character, they have to gather all of their relevant phrases/dice, roll them, choose the two highest numbers, and add them together to determine their end result. The more emotionally invested a character is in something, the more likely it is they’ll win.

There’s more to these argument mechanics. Characters gain stress in a relevant area whenever they lose a verbal joust, so if someone makes Zod angry he will gain an anger stress die, which other characters can add to their rolls when they’re playing off of Zod’s anger. If a player knows their character is probably going to lose an argument, they can just Give In to avoid receiving stress. There’s more, but that’s probably 80% of Smallville gameplay.

Characters in Smallville don’t really have normal stats. This is interesting. In a regular RPG, stats essentially help create the fiction of the world; smart characters have higher INT, so they’re more likely to succeed in situations that require intelligence. This naturally means that, if someone read a series of session recaps involving this character, the reader would probably notice over time that this character was the most intelligent member of their party because of how their stats are reflected in the outcomes of events.

In Smallville there’s an even more direct relation between its equivalent of stats and the end results, because they work on more narrative terms. Smallville was not the first game to have a concept similar to this, but the implementation of these ideas still feels pretty groundbreaking here.

Something interesting about Smallville is that it has a brief chapter on how to play the game online. I’m assuming a primary target audience of Smallville was women who wrote Smallville fanfiction, and if that was the case, it’s a nice wrinkle to include an online RP tip chapter. I would love to know how many games of Smallville were basically AU fanfics written collaboratively online.

Before we wrap up I should quickly mention that the GM in Smallville is referred to as “Watchtower”, which is literally the worst alternative GM title I’ve ever heard.

Ed Grabianowski made an observation about Smallville in his writeup on the game contemporaneous to its release; it might be the only superhero RPG that focuses more so on relationships than superpowered battles. Masks [the PbtA one] and With Great Power are probably the only other games that come reasonably close. Smallville definitely fills a unique niche; CW superhero shows are basically their own subgenre at this point, and Smallville is the only game that really attempts to emulate them. I personally have never watched a CW superhero show, but I still would love to play Smallville.

Smallville has been out-of-print for nearly 15 years, and I think it’s safe to say that it’s never coming back. If the Cortex Prime system was ever made open, and someone released a genericized version of Smallville, I would seriously consider buying it.

If you want to learn more about Smallville, I recommend listening to the System Mastery episode about the game. Smallville is System Mastery near their best; the hosts are legitimately interested in the game and highly knowledgeable about the source material, and so the mechanical breakdown is more informative than usual. You probably can’t learn Smallville just by listening to their episode, but you can certainly learn what to expect.

Further Cannibal Halfling reading on Cortex: 1, 2

Savage Worlds Supers

I shared the original article I wrote on Reddit and someone asked me why I didn’t include Savage Worlds Supers. It was a good question; Savage Worlds is a solid rules-lite system with some nice mechanics. I’ve heard people compare Savage Worlds to GURPS because of its point-buy advantage / disadvantage stuff, but some elements, like the exploding dice and “cinematic” focus, remind me a lot of D6.

Savage Worlds seems to be the most popular “cinematic” generic system at the moment, especially if we’re mostly talking about more traditional systems. It’s definitely flavored for a pulpy, two-fisted approach, which is usually desirable for a superhero context. I’ve also heard people say that it’s better for more “street level” play, so probably better for feet-of-clay Marvel-style heroes than the veritable gods of the Justice League [excluding Batman, of course].

If you’re not familiar with Savage Worlds, the most fundamental elements of the system are very simple. Characters have five attributes [stats], and instead of attributes having a number they have a die size. The smallest an attribute can be is a d4, but if a player puts points into an attribute it can go up to d12. d4 might sound too small to be useful, but since a normal action resolution roll would be roughly 4, that means a 25% success rate; bad, but not useless.

There’s a lot of other stuff in Savage Worlds, and I’ve heard that combat only really comes to life in this game when everyone has achieved system mastery. It seems like too much stuff to memorize for me, but you might feel differently.

The Savage Worlds Super Powers Companion is basically a list of additional options [advantages, disadvantages, powers, equipment, etc] tailored to the superhero genre. There are some pre-built villains here as well, and notes on base building. It’s something ideal for people who enjoy the Savage Worlds system.

I’m a lot more forgiving of generic systems with supers supplements not having major genre-emulation elements. For starters, a big selling point is that the system will already be familiar to any prospective players. But, more importantly, generic systems usually allow for a degree of mixing-and-matching that you just won’t find in games purpose-built for specific things. There are exceptions; Savage Worlds Rifts apparently has characters who are so overpowered by normal Savage Worlds standards that they can’t really mix with other Savage Worlds books. But, for the most part, generic systems can allow for weird genre / setting combinations and edge cases.

All that being said, I can’t say that I’d ever want to use this. It’s not a bad thing that Savage Worlds Supers isn’t highly optimized for superhero stuff . . . if you’re a fan of Savage Worlds. I personally think the system is fine, but I’d rather use PDQ or FATE. And, if I wanted to do a weird mashup thing that really took advantage of generic systems, it’s my understanding that GURPS makes a much more concerted effort to keep their product line compatible than Savage Worlds.

But, if you’re already a fan of Savage Worlds, this is probably a solid option. There’s a Pokemon fan game that uses Savage Worlds as a basis, and I’d love to play it sometime. But Savage Worlds is not what I’d want to use for a superhero game.

Masks

This is not the Masks you’re thinking of. Blacky the Blackball, operator of Gurbintroll Games, created a free Marvel Super Heroes retroclone that attempted to find a middle-ground between that game and Icons. It’s basically Marvel Super Heroes, but with some FATE-isms. This is how Blacky describes the game5:

Masks is a mash-up of ICONS and [Marvel Super Heroes]. It uses the [Marvel Super Heroes] ranking system and areas for combat, but uses ICONS-style die rolling and rank comparison instead of a [Marvel Super Heroes]-style table and uses ICONS-style determination instead of [Marvel Super Heroes]-style karma.

I talked about Marvel Super Heroes clones last time, and was quite dismissive of them in concept. Blacky has made a different, much more faithful clone, called FASERIP, which I don’t really have much interest in. And if you’ll remember from last time, there’s another straight-ish clone called Astonishing Super Heroes that advertises itself as using a “revamped Karma system”.

I’ve listened to the System Mastery episode on Marvel Super Heroes, and so I now know what the original Karma system was like; it basically penalized players for doing things like killing enemies and causing property damage. It was also an EXP system, and players could cash in Karma for short-term bonuses, which is always a divisive mechanic.

I still don’t know what Astonishing Super Heroes did exactly, but this aside on other Marvel Super Hero clones that I already talked about has gone on long enough, so let’s circle back around to Masks. The thing that interested me in Masks was its FATE-y approach, which is really quite simple; characters have positive and negative Aspects they can invoke to spend or gain points6. Points can be spent on things aside from invoking positive Aspects, like contriving a coincidence or getting a bonus to a general roll.

Masks is a pretty rules-lite game. The character creation and basic mechanics take up the first 53 pages, with the rest of the book being descriptions of powers that the character creation stuff at the front refers to. Character creation in Masks is fun and simple; it seems to be inspired by Icons character creation, but I like the changes Blacky made. The writing style in Masks is very clear and doesn’t make things confusing, even if it uses the extremely British “Nous” as a name for an attribute, instead of something a bit more transatlantic.

Even if Masks is easy to understand, it gives off the vibe that it’s meant for people who already know how to run an RPG. There’s no advice on running supers campaigns, or anything else to that effect, to be found. There is some helpful advice around mechanics [e.g. a warning symbol for powers in character creation that might prove problematic depending on the campaign, such as precognition], but obviously that’s not the same as dedicated chapters for a GM. A minor quibble, when we consider the kind of person most likely to be reading a PDF tucked away on some guy’s retroclone site.

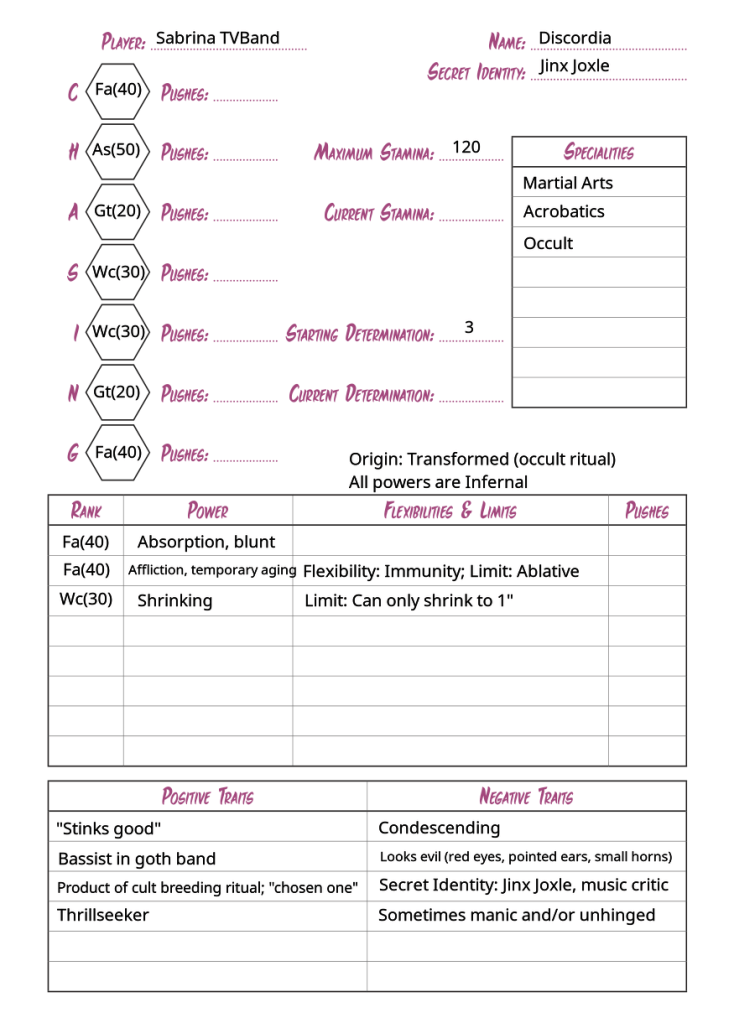

I decided to make a Masks character to test out the character creation. I feel like I was a bit lucky as far as getting rolls that worked well together, but I think it’s safe to say that the large majority of supers games with randomized character generation are liable to occasionally produce weird results.

My Masks character’s name is Jinx Joxle. Joxle is a witch’s fail daughter, and she has infernal powers; she can absorb any kind of blunt attack, temporarily age people by touching them, and shrink. She lives inside of a matriarchal coven’s inconspicuous base, and was the product of a Bene Gesserit-type breeding experiment. She has a music blog where she reviews awful darkwave music. She plays bass in a goth band, and all of her basslines are too noodly and treble-y. She looks a little demonic, but it’s nothing a hat and sunglasses can’t conceal.

She might sound like a supervillain, because she gets her powers from an infernal source and is a member of a coven. She joined the super community because of her thrillseeking nature, and fights villains because she usually finds them gross and annoying. A flimsy moral compass, but she’s not an antihero. She is condescending, though, because her coven tells her she’s the “chosen one” [she’s not].

The process of creating the character was simple; the clarity of the writing made it a breeze to work through each step, and the bulk of character creation was spent on the creative side of things. My only complaint is that having traits be either positive or negative feels limiting. While the game does say that positive traits can sometimes be negative [and vice versa], it would be good if there was space on the character sheet for more neutral traits, which is what Aspects in FATE are generally assumed to be.

This was my first time making a character in a superhero RPG, and I think I’m going to always at least try making a random character; it’s a lot of fun in this genre.

Having listened to the aforementioned System Mastery episode on Marvel Super Heroes, Masks doesn’t seem to borrow much from the Advanced version of the game. Masks doesn’t use a big table for action resolution the same way Marvel Super Heroes does, even if you’re still going to end up referring to a big table quite often7. In Masks, each stat has a “rank”, and action resolution either means comparing ranks in a static way [no dice rolls] or doing rolling using FUDGE dice, with negatives and positives adding or subtracting a relevant rank respectively. Only the PC rolls dice when in contest with an NPC; because of how the math works, there’s no reason to do opposed rolls. There’s more, like degrees of success, but that’s the gist of it.

That being said, you’re still going to want to know what rank a knife should have in relation to a gun, and also probably have a cheat sheet describing what different degrees of success mean for different kinds of rolls. Each power has its own descriptions for what happens with different degrees of success, and players will want to have references for those as well. There’s a master table at the very end of the book that covers almost everything I just mentioned, except powers, which inexplicably has a giant black non-printer-friendly border around it. It would only make sense as the back cover of a PoD book.

[Masks is] a fine game and I’m very proud of it, but sometimes I don’t want to be messing about with FATE style aspects and the like. – Blacky the Blackball

Unfortunately, Masks isn’t available for purchase as a PoD book. This is partially because the game uses art released under a non-commercial license, but also it seems that Blacky views FASERIP as being his definitive superhero game statement. This is unfortunate, because I do think Masks is a game that deserves a spotlight.

Masks is based off of perhaps the most beloved old-school rules-lite superhero game, Marvel Super Heroes Basic. The innovations inspired by Icons are welcome, and I enjoy the slight changes Masks made in turn. The way I see it, Masks is the best supers game that’s heavily inspired by Marvel Super Heroes.

Would I actually play Masks? It depends on how often I get to play superhero RPGs; games like Truth & Justice and Daring Comics, where things are looser, which in practice means more like actual comicbooks, are more appealing to me conceptually. Those are the games I want to play first. But I could certainly see myself playing Masks eventually to mix things up.

But that’s just me; if you want Marvel Super Heroes except with Aspects and FUDGE dice I highly recommend downloading the free Masks PDF and seeing if it’s to your taste. If you want a simple trad game but with FATE Aspects, Masks is for you.

Capes

Capes is an early GM-less game from 2005 that intrigues me more than most GM-less games. From what I understand the game uses metacurrency systems where tokens change hands depending on if characters are doing genre-emulation things or not, and this is how players keep each other in check.

Capes seems like a game that really tries to emulate superhero storytelling, but it also seems like a game that doesn’t exist anymore. The game’s Indie Press Revolution page only sells the physical book, which is out of stock, and the publisher’s website seems like a hole you can drop money into; it’s one of those situations where you buy the game and they email you the PDF manually, but I get the feeling nobody is listening anymore. There is a lite version available for download, at least.

There are obviously a lot of old physical games that have never been scanned, but there’s something uniquely tragic about a game that used to be available in PDF form essentially vanishing like this. I would’ve read this one, if I’d had the chance. Surprisingly there seems to be a French translation available, but only of the lite version.

Going Deeper Into Games From Last Time

Anyways, those are some of the games I felt I needed to discuss here that I hadn’t already mentioned; I’ll discuss another four in part 2. Now it’s time to move onto the games that I touched on last time and thought were promising. As I said before, I’m going to look at the rulebooks for all of these games and make more personal impressions, instead of going solely off of reviews and forum posts. To be clear, I think if people know what they like they can get a very accurate picture by reading reviews and hearing impressions. But I’m going deeper here for a variety of reasons; to make a better resource, to learn more about game design, and for possibly running games in the future.

I’m going to skip Masks [the PbtA one], because I don’t think I could provide any necessary insight about Masks considering it’s probably the most popular and widely discussed supers game on the market right now.

Risus

Risus, the “anything RPG”, is a simple rules-lite universal system, designed for comedy, but in practice it can be used for anything. The current edition of the game is only four pages long, and it can be downloaded for free, and so I won’t get too deep into the mechanics here.

Risus was revolutionary in its design, and its influence can be felt in later systems like PDQ and FATE. Essentially players are given 10 six-sided dice to divide between multiple cliches. Cliches can be “real” cliches like “mad scientist”, or they can be something understood between players without actually being a real cliche, like “on-fire guy”. Unless a player has GM permission, they cannot assign more than 4 dice to a single cliche to begin with. These dice are then rolled in opposition, or against target numbers.

This is extremely simple stuff, but when you consider that characters have to approach problems with their cliches, you can start to see what makes Risus such a special game. In Ghostbusters characters had special talents that sometimes could provide a hefty bonus to a roll, but they always had generic stats to fall back on. In Risus, talents and regular stats are one in the same [is this reminding you of anything?].

When I first tried creating a character in Risus, I had a hard time wrapping my head around cliches. Someone’s instinct when choosing cliches might be to choose closely related cliches, which doesn’t really make sense in practice; what goes with mad scientist? Science whiz? Madman? You need to choose multiple, seemingly unrelated cliches, because that’s how characters actually work if they aren’t completely one-dimensional. Here are a few example characters I made.

Spider-Man

Powers of a Spider (4)

Science Whiz Nerd (3)

Unexpected Casanova (3)

Superman

Flying Brick (5)

Journalist (3)

Farm Boy (2)

Rayne

Vampire Hunter (4)

Femme Fatale (4)

Dhampir (2)

Creating Risus characters is quite simple, and adapting pre-existing characters into Risus is even simpler. It should be noted that older versions of Risus [such as 1.5] allowed for the use of “funky dice” to replicate superhuman abilities. Dice were purchased using a point system, where each die cost how many sides it had [d6 cost 6 points, d8 cost 8, d10 cost 10, etc]8. Risus recommends 200 points for making a superhero, but that seems like a bit much for Spider-Man. Here he is again with a 150 point build:

Spider-Man

Powers of a Spider (4d20)

Science Whiz Nerd (4d12)

Unexpected Casanova (3d6)

To support these expanded power levels, version 1.5 of Risus also included an expanded target number list to help out GMs. According to this list, if Spider-Man rolled an 80 he’d be able to throw a little less than 15,000 loaded trains, and so I probably should’ve reduced the number of points even further to 100 for a team of Spider-Man-level characters.

If you were wondering why funky dice rules are no longer included in Risus, S. John Ross described them as being “a kind of evolutionary blind alley for Risus at the core level”. This is understandable; Risus has a very “d6” ethos, at least in my eyes. Polyhedral dice just seem antithetical to the game’s whole vibe. Maybe that’s not what Ross meant, but I think I understand why they aren’t in the game anymore.

Risus is really great for certain kinds of games / genres, even outside of a one-shot context. While you can create literally any kind of character in Risus very easily, which is important for a superhero system, there are other systems, like the aforementioned FATE and PDQ, that also allow for very flexible character creation while having more mechanical depth. I’m not trying to imply Risus is a flimsy game; it’s just that it’s built around a certain play philosophy that emphasizes scenario design and simple rules conducive to creating humor. Risus is, in many ways, genericized Ghostbusters, and I don’t think Ghostbusters is the best basis for a superhero game.

I’ve reached the same conclusion as I did last time; I would love to play a Risus superhero one-shot, but for something longer, I’d want a system with a little more optimization for superhero-related play.

Icons

Icons is a supers game by Steve Kenson. The game is inspired by Marvel Super Heroes, with elements from FUDGE, and also apparently Marvel SAGA, although I have no real familiarity with SAGA. Steve Kenson is best known as the creator of Mutants & Masterminds, but he’s had a very extensive career, especially in the supers field.

Action resolution in Icons is simple. It’s described thusly:

Effort (Acting Ability + d6) – Difficulty (Opposing Ability + d6) = Outcome

Basically this means a player gets their relevant stat and adds a d6 to it, and the GM does the same for the opponent opposing them. Not everything is opposed rolls; Difficulties can be static. What’s interesting about this is that literally adding a d6 to a stat like 8 removes a lot of swinginess from the game, even if only one die is being rolled. Anyways, the number rolled by the GM is subtracted from the roll made by the player to determine the “Outcome”, which is used to see what degree of success the player received. There are seven degrees of success, which is a lot, but formalizing rolls with this equation makes it more manageable than it could otherwise be.

Since Icons and Masks are both heavily inspired by Marvel Super Heroes, they are both very similar games. Mechanically they have differences, sure; Icons uses d6es and Masks uses FUDGE dice. But if you look under the hood, they’re working very similarly. Icons basically has Ranks as well, except they’re called Levels instead.

The biggest difference between Icons and Masks, the way I see it, is that Icons has a bunch of GMing advice. Everything else is basically minor flavor and differences in presentation. It’s kind of like comparing Basic Fantasy and Old School Essentials; sure, these are not literally the same . . . but they basically are. Of course, while both games are retroclones of Marvel Super Heroes, a lot of things that Icons brought to the table first, like Determination, were adopted by Masks. So this isn’t entirely analogous to two B/X retroclones, because Masks is clearly post-Icons.

Of course, GMing advice isn’t nothing, and the advice in Icons is very good. Icons introduces a thing called “Pyramid Tests”, which is an interesting way to conceptualize challenges. The book also has notes on writing adventures, comicbook tropes, and even a brief procedure for creating a comicbook universe.

Anyways, here’s the character I rolled up in Icons. It should be noted that there is no official Icons character sheet; there are a few fan-made ones, but I’m just going to put text here instead.

Frankie Frunk was a normal human woman who was abducted by aliens. Her brain had been scanned, and she passed a highly esoteric test that made the aliens decide to give her a special device. This special device allows her to fly, create disorienting lights, duplicate herself, and control people’s dreams. It also boosts her strength and other attributes above normal human levels. The device is a sleek metal object that covers her spine.

Frankie was tasked with becoming a superhero to help take care of any powerful supervillains that might someday move into space and try to do something to the aliens. She’s also tasked with doing some odd-jobs; they mostly seem very benign. Most people would refuse to become a superhero and do errands for aliens, especially people with such high willpower, but most people didn’t “pass” that aforementioned test.

Frankie Frunk

Origin: Gimmick

-Determination (2)

-Stamina (14)

-Stats

Prowess: 7

Coordination: 8

Strength: 6

Intellect: 5

Awareness: 6

Willpower: 6 (+2)

-Powers (4)

Flight (Movement) 5

Duplication (Alteration) 4

Dazzle (Offensive) (Lights) 5

Dream Control (Mental) 5

-Specialties (2)

Technology

Mental Resistance

-Qualities

Trusted by Alien Race

Headstrong Minor League Baseball Player

Brusque Protector

Character creation was basically fine, but I preferred making a character in Masks. This is mostly because I hit some small snags while making a character in Icons, which I attribute to the layout of the book. I’m not the biggest fan of Icons’s layout. The book is digest size, for starters, which means individual pages only have enough space to say one or two useful things. Blurbs and asides often take up an entire page, instead of a small portion of a single page. This is a pet peeve of mine; for a small game like In a Wicked Age a small book makes sense, but more substantial9 TTRPGs should at least be at least 7” x 10”, preferably 8.5” x 11”.

But things feel more poorly conceived on a fundamental level. What happens if I go to the page with the Determination heading? Instead of saying what Determination Points can be spent on, it just tells me to look at a different page later in the chapter, without even providing a page number. This is more personal, but I also don’t like the visual design of the book; I think the art looks bad, and the bubbles at the bottom of every page are off putting.

A big negative for Icons is that it’s ridiculously expensive to buy a print copy. $44 for a 232 page 6” x 9” book? I’m not sure if I could ever justify buying that, especially since I’m not a fan of the digest form factor. I realize that Icons uses the premium color printing option, but my response is that they should’ve made a black and white version available as well, or even a non-premium color version. I should clarify that I think $15 for the PDF is fair, and pretty normal for a book of this size; I’m only referring to the PoD pricing here.

I have to admit, I was quite off-base with lumping Icons in with the other FATE-inspired games in my original post. While Icons does have Aspects, and Determination Points, much like Masks it’s a completely different beast when you take everything else into account. Thus far, Icons is the game where I feel like my comments in the original piece I wrote were the most “incorrect”; it’s a completely different kind of game than I thought it was going to be.

Something that I wasn’t expecting is that I think I’d rather play Masks than Icons. While I do prefer the zones movement approach taken by Masks, and also its FUDGE dice approach, I think presentation is also a big factor here. It also helps that Masks provides a big useful table that more-or-less explains everything at a glance. I’m not actually sure if Masks can really even be called more “traditional” than Icons, but the ways in which it is more trad feel like ways in which the gameplay is streamlined rather than ways in which the mechanics restrict gameplay.

I feel like I’m ending a little too negative on Icons, and so I should once again emphasize that, as much as Masks and Icons are both retroclones of Marvel Super Heroes, Masks is also heavily inspired by Icons. And I prefer Masks to Icons maybe 10%. I don’t think Icons is a bad game; it’s just more trad than I thought it was going to be, and I also think Masks supplants it in its niche. That’s just me, though.

Daring Comics

Daring Comics is an all-in-one book that presents a version of FATE Core optimized for superhero games. There’s another similar book called Wearing the Cape, but Daring Comics is the FATE implementation I decided to read for this piece.

If you’re unfamiliar with FATE, I recommend watching this Dungeon Newb’s Guide video explaining how it works. I keep linking to this guy’s videos because they’re all very well made and informative, if you can ignore the typos. The Book of Hanz is another great FATE resource.

Anyways, the first two chapters of Daring Comics is mostly the basic FATE stuff explained in the aforementioned video. It helps that Daring Comics is full of examples for anything that might be confusing to a new player, tailored to the superhero genre.

Something immediately noticeable about the book is that the presentation is a bit lacking; the layout is extremely basic, and the art is, sometimes, quite poor. Ideally presentation is exceptional, but there’s nothing wrong with presentation that is merely competent. Daring Comics is a little ugly, and there are some weird editing mistakes, like the part explaining what FUDGE dice are being repeated twice. At least once Daring Comics commits the biggest layout sin imaginable; having a header appear at the very end of a page.

Continuing with layout, Daring Comics does another thing that really frustrates me, which is have a massive list of powers right in the middle of the book [pages 84 to 125], instead of placing it at the very end like Masks [the Gurbintroll one]. There are actually a bunch of different lists in the middle of this book, separating the essential beginning chapters from important later chapters, like Actions and Outcomes, Comic Book Action, Running Daring Comics, Telling Stories the Comic Book Way, and Advancing the Series. I don’t know what compels people to design books like this.

The third chapter is called Series Creation, and it details how players can work with a GM to create a setting10 while providing information on power levels and tones. Power levels is what you’d expect; it tells you how many starting points players receive if they want to play grounded Marvel style heroes, powerful Justice League types, or something more cosmic. Tones determine how severely things affect player characters, with “Near Realistic” having very severe consequences and “Four Color” consequences resolving much faster. I like this, because often these notes on desired tone are solely there to help GMs and players reach a mutual understanding, but there are some mechanical effects outlined here.

There are more chapters and rules in the book devoted to genre emulation and such, for things such as super team Aspects, collateral damage, and fastball specials. A personal favorite; a brief section in Telling Stories the Comic Book Way detailing how to create situations that make superheroes fight each other [misunderstandings, mind control, etc]. I don’t know if FATE games have a reputation for being shovelware, but it needs to be said that Daring Comics is the furthest thing from the FATE SRD with the bare minimum of flavor text; everything is tailored specifically to the superhero genre here.

The way powers work in Daring Comics is that they are controlled by Skills. For instance, if a character has a Magic, Mental, or Power skill, this can allow them to have the Air Control power. Daring Comics includes a two page character sheet that’s distinct from the regular FATE character sheet, to accommodate differences like this. It also has a sheet that allows the GM to record four supporting cast members and four rogues, as well as team and “series” sheets.

I probably missed the part where Daring Comics kicked somebody’s Fate puppy or something, but I really like its version of Fate. – ruckusmanager

When researching FATE supers games, I noticed a lot of people seemed to feel that Daring Comics made some design choices that were antithetical to FATE principles. Reading the book, I feel like this is inaccurate or overstated. Daring Comics, with its various point-buy systems for different aspects of character creation, is perhaps less “loose” than the majority of FATE games. But objecting to this element of Daring Comics really feels like making a mountain out of a molehill. The game is a self-described toolkit, which in turn means it’s up to the GM to remove extraneous things they don’t want, within reason. It should be noted that the book includes an entire appendix chapter called Turning the Dials.

Daring Comics is, if not dense, certainly a very long and meaty book. So I mostly skimmed the book for the purposes of this piece, taking care to read at least every heading [ignoring the massive lists of skills, stunts, powers, and gear]. From what I saw, Daring Comics is an extremely complete superhero game; there’s no variety of genre emulation / GMing advice you’ll see in a solid superhero RPG missing here.

If you want a version of FATE optimized for superhero play, Daring Comics seems like a great option in all the ways that matter. It would be nice if the book had better presentation, but obviously that’s not as important as the quality of the gameplay. That being said, it does make potentially purchasing a physical copy less appealing than it should be. I really wish the editing and visual design were a touch better, because this should be an easy, unequivocal home-run.

Spider and Man

You’re probably wondering how much more I could possibly have to say about a Lasers & Feelings hack. The answer is, admittedly, not very much. I can only really think of how I would personally GM the game. I’m going to quickly copy the GMing advice here in its entirety:

Play to find out how they defeat the threat. Introduce the threat by showing evidence of its recent badness. Before a threat does something to the characters, show signs that it’s about to happen, then ask them what they do. “The Green Goblin charges the pumpkin cannons on his glider. “What do you do?” “Kingpin pours you a glass of whiskey and slips his arm around your waist. “What do you do?” Call for a roll when the situation is uncertain. Don’t pre-plan outcomes—let the chips fall where they may. Use failures to push the action forward. The situation always changes after a roll, for good or ill. Ask questions and build on the answers. “Have any of you encountered a Skrull before? Where? What happened?”

The game seems to want the GM to go in with as little prep as possible, but I would definitely want to prepare a few things in advance, in a way I can only describe as being Maid RPG-esque. Which is to say, I’d want to think of a couple of “random events” in advance that I could insert into the game at any time. After opening a session with, for instance, an encounter with the Green Goblin, I’d want some bullet points relating to an encounter with Mary Jane, Black Cat, or J. Jonah Jameson prepared so I could keep up a desirable momentum. Nothing extensive, just notes about what these characters might want and where they might be.

Obviously planning out an adventure would be against the spirit of this particular game, but I’d like to think having some encounters prepared isn’t antithetical to the Spider and Man experience. If I ever GM’d Spider and Man, it would be great to have the players prepare their Spider-People first so that I could even tailor events to certain characters.

Anyways, that’s the end of Part 1. In Part 2 I’ll discuss Advanced FASERIP, Marvel Multiverse RPG, Heroes Unlimited, Marvel Heroic Roleplaying, Truth & Justice, and Sentinel Comics.

If you enjoy Sabrina TVBand’s writing, you can read her personal blog, follow her on BlueSky and Letterboxd, view her itch.io page, and/or look at her Linktree.

- Smallville and Marvel Heroic use Cortex Plus, but it’s my understanding that Cortex Plus and Prime have a lot in common, unlike the older Cortex Classic. ↩︎

- Cam Banks is not the person who gets to decide whether or not Cortex should be open; the system is owned by Dire Wolf Digital. ↩︎

- This session zero system inspired a system agnostic tool by Ewen Cluney called Entanglements, if that interests you. ↩︎

- Clark Kent would never threaten Lois Lane with his heat vision, you freak! ↩︎

- In Blacky’s original post he refers to Marvel Super Heroes as FASERIP, which would later become the name of his second MSH retroclone. ↩︎

- Much like in normal FATE, Aspects that normally would be positive can sometimes be negative in certain contexts, and vice versa. ↩︎

- In Marvel Super Heroes, players refer to a universal table to see what likelihood of success they have for a given rank. In Masks, you use the included table to see what kinds of ranks different things have, and also to see what ranks are compared for different kinds of contests and what degrees of success do. ↩︎

- If you were wondering, d4s are forbidden in Risus. ↩︎

- Saying “substantial” to refer to the amount of “stuff” in a game, not necessarily how meaningful the end play experience is. ↩︎

- Apparently the city creation stuff is similar to city creation procedures in the Dresden Files RPG. ↩︎

Longshot City is a superhero RPG that uses Troika system check it out.

LikeLike