Here are links to Part 1 and Part 2 in case you missed them. To open this part, I’d like to talk about hallmarks of the superhero RPG genre; there are some things I’ve noticed across all of these games that I think are worth highlighting.

Theater of the Mind Play

Superhero conflicts generally exist on such dramatic scales that using miniatures and grids often doesn’t make sense. Not only do most superheroes move very fast, but there’s also a level of verticality involved that can make things difficult to capture outside of a theater of the mind context.

Some crunchier games are designed more so for highly tactical miniatures play, but none of the games I’ve covered here thus far have presented grid-based combat as the default mode of play. The games that do use some kind of image reference, Masks, Advanced FASERIP, and Daring Comics, use zones, which are a lot looser. BASH, which I’ll cover in Part 4, is the only game I’ve read that presents grid-based miniatures play as default.

Low Advancement

Many superhero games do have advancement of some kind, but it’s very common for advancement in superhero games to be non-existant or very simple [e.g. more points in a metacurrency that refills at the beginning of each session]. This feels like a pretty tacit acknowledgement of how superheroes, generally speaking, don’t get much stronger unless they haven’t reached physical maturity yet, are still learning how to use their powers, or something dramatic happens [a further mutation, moving into a new body, etc].

Random Character Generation

Random character generation is not exactly uncommon in the TTRPG space, but in superhero games it seems to be more popular than in other genres, and also expected; I’ve noticed a handful of games release free PDF supplements related to random character generation, presumably to meet some kind of demand.

I think there are two core reasons for this; the first is that some popular early games in the genre had random character generation [Villains and Vigilantes, Marvel Super Heroes, Heroes Unlimited]. The second is that it’s a lot more fun in the superhero genre than in most other genres; there’s a certain blandness to rolling random stats for a barbarian in a fantasy game, but rolling superpowers to create a new superhero is a lot more exciting because it dips into fun and familiar superhero genre tropes.

Replicating Unique Characters

This is as much something I’ve noticed while reading forum posts about superhero RPGs as it is something I’ve seen in rulebooks, but superhero RPGs generally make an effort to support the replication of weird characters, and system wonks love to stress test these games by making these characters.

Green Lantern is a big one, because his ring can create objects and he has to recharge it using a lantern. Spider-Man has a weird group of powers, with his web-shooters being a gadget rather than an actual power. There aren’t many characters with weather control as a power that I can think of, but because Storm exists there are a lot of games that include weather control. I don’t really think of duplication as being an especially popular superpower, but for whatever reason, almost every game seems to include duplication.

There aren’t really a ton of characters that use armored suits like Iron Man either, but most games also include “powers” for recreating Iron Man-types.

Batman

Relatedly, almost every superhero RPG includes some kind of mechanic that allows characters to have fewer powers in exchange for being able to have more skills, or whatever the equivalent is in a given game. It’s also not uncommon for games to give characters with no powers or weak powers extra points in a given metacurrency, to allow them to keep up with high powered superheroes.

Something that can be problematic is that some games don’t allow a character to have literally no powers. In these games “real” powers must be used as pretend “trained” abilities [in Advanced FASERIP a character like Batman might have the “mind shield” power]. Conversely, some games that are more narrative-y treat trained abilities and powers the exact same way mechanically.

Silver Age

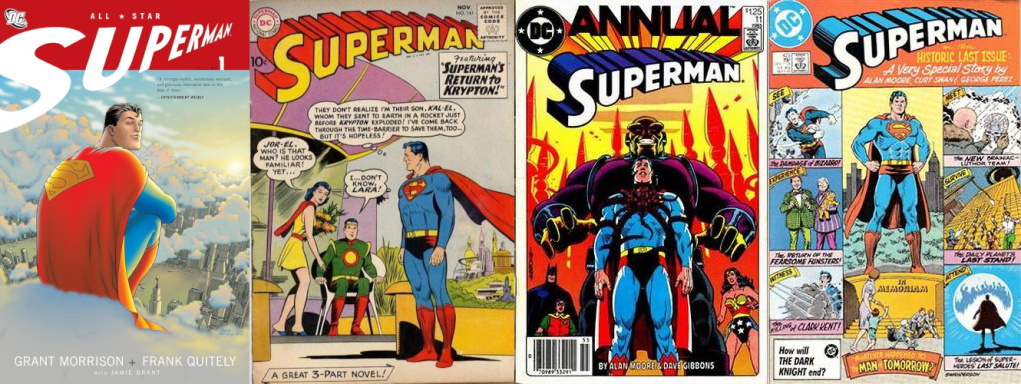

For some odd reason, the overwhelming majority of superhero RPGs seem to emphasize a silver age focus. This is odd because almost all of these games do nothing to actually reinforce this on a mechanical level; the games can be used for any era of comics, with all of the flavor coming from the GM and players.

The funny thing about the silver age focus is that they’re clearly talking about the “Marvel Age” of comics, because I’m not seeing a lot of DC-flavored silver age stuff. Sure, some of these games will throw in a talking gorilla, but that’s not the real shit.

Games I Haven’t Talked About

Astonishing Super Heroes

I’ve mentioned Astonishing Super Heroes a handful of times while talking about Marvel Super Heroes retroclones. I realized a few days ago that I’d purchased ASH in the TTRPGs for Trans Rights in Texas charity bundle, and so I decided to actually read it instead of mentioning again how I didn’t know what “revamped Karma system” meant.

It’s worth mentioning that Astonishing Super Heroes is already “obsolete”; the game is being used as a foundation for a new, more complete Marvel Super Heroes retroclone called HEROIC: The Roleplaying Game.

HEROIC is a Neo Clone of the old-school MSH Advanced game by TSR that combines aspects of modernization as well as parts of the Astonishing Super Heroes RPG by Tim Bannock. – HEROIC Backerit page

I’ve already discussed Marvel Super Heroes quite extensively while talking about Masks and Advanced FASERIP, and so while talking about Astonishing Super Heroes I’m only going to be focusing on what it does differently; there will be no discussion here relating to basic mechanics like the action resolution table.

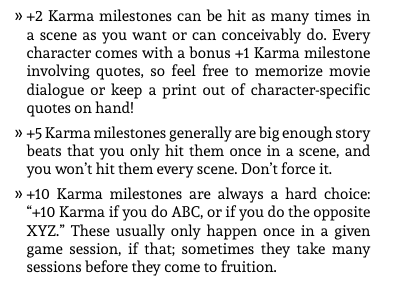

The thing that immediately stuck out to me while looking at Astonishing Superheroes is that it uses the term “datafile” instead of “character sheet”. This is notable because datafile is a Marvel Heroic term, and it turns out this is not a superficial reference. The game adopts the “milestones” concept, where characters gain different amounts of Karma depending on if they accomplish certain personalized tasks. By default characters can gain +1 Karma if the player quotes dialogue from superhero related media, which is a bit silly.

The ways in which Karma was earned and lost in Advanced FASERIP were quite detailed; allowing people to sacrifice themselves made heroes lose Karma, and heroes gained Karma by rescuing people, for instance. Astonishing Super Heroes seems to boil it all down to the milestone system, which is disappointing; it’s easier to keep track of, but also provides less genre reinforcement. It’s also less exciting than the Aspect stuff in Masks. Milestones also changed in Marvel Heroic, and in this game they stay the same, which makes them easier but also less compelling.

The kinds of things Karma are spent on in Astonishing Super Heroes are not very different in practice than the kinds of things players can spend metacurrency on in Masks or Advanced FASERIP; boosting an attack, preventing oneself from dying, etc. Something Masks has that neither of the other clones have is the Dramatic Editing-esque “Contriving Coincidence”.

I also really like how Advanced FASERIP ties Karma spending into advancement, but at the same time, I prefer how Astonishing Super Heroes makes everything Karma-related cheaper, and seems to make the numbers smaller in general.

The one thing Astonishing Super Heroes does really excel at is rules about social interaction; the Gurbintroll clones don’t really have much text related to social interactions, and so the ideas and optional rules in Astonishing Super Heroes really provide something interesting. And since all of these games are largely compatible, it would probably be a good idea to print out the social pages from Astonishing Super Heroes for use with Masks or Advanced FASERIP if you happened to get the game in a bundle or something.

I was about to recommend Astonishing Super Heroes for groups that like all of their players to own copies of a given book, because the print-on-demand cost on DriveThruRPG is a very affordable $12.95. But then I noticed something; the book doesn’t include character creation or advancement-related stuff. Everything related to those topics was meant to be included in a separate book, Spectacular Origins, that was never finished. An unfinished beta PDF is available on itch.io, unfinished being the key word here. At least it includes a long list of generic milestone goals, which I had wished Marvel Heroic had.

So, ultimately, I feel like talking about Astonishing Super Heroes was kind of a waste of time. It’s an incomplete document, and right now it ultimately just hints at what HEROIC might bring to the table. Masks and Advanced FASERIP both are better options.

Four Color FAE

Four Color FAE is a small document designed to add supers stuff to FATE1 Accelerated. If you’re not familiar with FATE Accelerated [also known as FAE], it’s essentially a stripped-down version of FATE Core that swaps out some modular elements, most notably replacing Skills with Approaches.

Skills in FATE Core are . . . skills. If a character is good at something, they get a bonus when doing something related to it, without having to spend FATE Points. Approaches are looser and more general, and are used much more often. The six approaches are Careful, Clever, Flashy, Forceful, Quick, and Sneaky.

In FAE, characters have one Good (+3) Approach, two Fair (+2) and Average (+1) Approaches, and one Mediocre (+0) Approach. I wish that, by default, FAE did what PDQ does and have multiple distribution options, for instance having one Superb (+5) approach and a Terrible (-2) approach with the rest being Mediocre (+0)2, etc. But it wouldn’t be difficult to simply hack this option in if you want it.

Approaches are very broad. To give you an idea of how an Approach will almost always be relevant, here’s how Careful is described:

A Careful action is when you pay close attention to detail and take your time to do the job right. Lining up a long-range arrow shot. Attentively standing watch. Disarming a bank’s alarm system. – FATE Accelerated

I’ve heard many people say that FATE Accelerated is best for games where every character is a variation on the same thing; an entire party of witches, or ghostbusters, or, in this case, superheroes.

Four Color FAE is a document that can be downloaded for free from DriveThruRPG in PDF form, or read online. Very annoyingly, the PDF has a ton of white space because of how the PDF was generated from the GitBook file, turning a very short document into a 61 page behemoth.

Four Color FAE is extremely simple; characters need to have one Aspect relating to their superpowers, and then they have a list of Power Facts, which basically says what they can or cannot do with their powers. Weaknesses and such are also included in the list of Power Facts. This list puts everyone on the same page when it comes to what characters can and cannot do in the fiction.

Powers don’t change your choice of actions, approaches, or rolls. Instead, they give you permission to make rolls in new situations. For example, a heroic adventurer archaeologist in a pulp campaign doesn’t get an Overcome roll to Forcefully lift a 10-ton rock from his path – he doesn’t have narrative permission to even try. But the superhero Mack Atlas does, because he has a power fact saying that he has super-strength. – Four Color FAE

The thing about FATE is that its target numbers don’t work like in Risus or PDQ. In those systems, a character can’t do something because they can’t roll high enough, simple as that. In FATE, characters can’t do things because they obviously can’t [or because they could and they failed their roll anyways]. Different approaches are better for different games, but this approach does have the convenient side effect of making power scale stuff very easy to manage with a mature group of players.

The paragraph I just quoted is probably the most important part of Four Color FAE, but there’s more important stuff in the document. It discusses how to handle powers that raise certain questions [duplication, super speed, telepathy, time travel, etc]. There are some notes on GMing superhero campaigns that feel pretty rudimentary after reading so many superhero RPGs, but the advice in itself is not bad. Finally, there’s a list of optional and alternate rules, perhaps most notably a bit on power levels.

There’s also a page at the very end with links to various FATE supers related pages, and of course they’re almost all Google+ links and Google Drive files that are no longer accessible.

I previously talked about Daring Comics in Part 1, probably the most detailed and extensive FATE supers book. Using Four Color FAE with FATE Accelerated is the opposite extreme; very lightweight and simple. There’s a massive gradient between those two extremes; Venture City, Wearing the Cape, the Supers section in the System Toolkit, as well as any specific permutations of FATE mechanics made by a specific GM.

I think Four Color FAE is a great option for people looking for fast and simple supers play. The only generic games here less complicated are Risus, and maybe also Truth & Justice and the following Supers!, with Four Color FAE being a less traditional option than those other games. Notably, both FATE Accelerated and Four Color FAE are free, with a PoD copy of the former only costing around $3~, which means an entire group can be furnished very affordably.

Going Deeper Into Games From The Original Article

Supers! RED and Triumphant!

Let’s first go over some history here; Simon Washbourne created Supers! in 2010. At some point he sold the rights to the system and Hazard Studio released Supers! Revised Edition [better known as Supers RED] in 2014. In 2013, Washbourne created a different superhero game called Triumphant!, which received its own revised edition in 20213.

I’m going to talk about the original version of Supers here, because it only costs a dollar on DriveThruRPG. Some people seem to prefer the original version because it’s a bit looser and less defined, but the consensus seems to be that Supers RED offers a few subtle improvements. Even this writeup, which is highly critical of many changes RED made to the original version, seems to view it as being an improvement overall, and they also say it might be the best generic supers system they’ve ever seen4.

Supers is a very simple game. Players are given a pool of dice that they can assign between Resistances, Aptitudes, Advantages, Disadvantages, and Powers. Dice that aren’t assigned are put into a Competency Pool, and for games with characters of different power levels, this pool is what gets boosted for weaker characters.

There are four different kinds of Resistances, two physical and two mental, which means there’s a level of detail to how characters roll for defense.

Aptitudes are skills, while Advantages are good things that aren’t skills [having allies, being attractive, etc]. Characters have to take a Disadvantage with every Advantage, or they can take an extra d6 for a Power if they take an unpaired Disadvantage.

Powers can have complications that make them up to 2d6 stronger, and Powers can be used to attack or defend in this game, as long as the player can justify it.

What makes Supers combat tactical is that characters cannot use any of their Powers more than once per round. A character might use a weaker Power to attack so they can use a stronger Power to defend when they’re low on Resistances, for instance.

There are some interesting wrinkles here. Non-superhuman characters, like Batman, cannot have more than 3d6 in a Resistance, because that’s the maximum human level. Instead these characters can put extra dice in and keep the 3 highest, dropping the others. The list of non-opposed target numbers in this game does helpfully delineate “The Exceptional Line” and “The Super Line”.

During character creation there is a guided method that tells players a maximum number of dice they can place into given stats and such, but optionally players can just be given a number and told to assign their dice however they’d like.

Supers is a very simple game with enough mechanical heft to feel meaningful. There are some superhero games that use variants of the actual West End Games D6 system [including one made by WEG, DC Universe]. Supers feels like Washbourne took a few fundamental liberties with the D6 system in the service of making a game highly optimized to the genre it’s imitating, while still strongly resembling D6. I was originally planning on reviewing a D6 system game5, The Mighty Six, but after looking at Supers I don’t feel as compelled to.

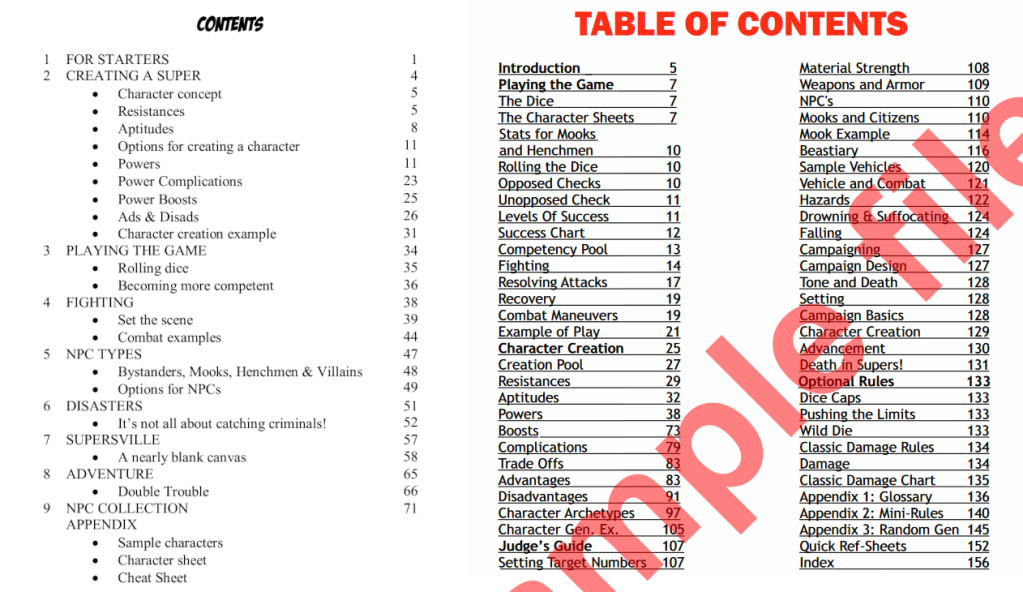

Here are the table of contents pages for Supers and Supers RED, to give you an idea of the differences between the two. Take note of added random character generation and miniatures rules in the appendices. The optional Wild Die rule, which seems like a very WEG-y touch, interests me immensely.

Supers doesn’t seem to have a ton of genre emulation stuff outside of the fact there are superheroes in the game, but somehow I’m not especially bothered here. The core mechanics are so elegant; it still would’ve been nice to see something analogous to the procedures in Truth & Justice [which are possibly hidden in one of the GM sections in Supers RED].

I didn’t have time to also read Triumphant, but I’ve done some reading on what the differences are, which I’ll outline here. From what I understand, it’s largely the same game but with some notable differences.

[Supers Red and Triumphant] are like 85% the same but some core differences will make you choose one over the other. – superyuyee

Perhaps the biggest change Triumphant makes is that, instead of using d6 pools, it uses a die-step system where dice get larger as powers get stronger. I’m the kind of person that generally prefers a dice pool to rolling a single die, and so already that sounds like a negative for Triumphant relative to Supers. The game is also described as being more tactical in focus than Supers, which can be a positive or a negative depending on where your priorities lie.

Something else that differentiates Triumphant from Supers RED is that it includes some rules for teamwork-related stuff in combat, which is surprisingly rare in superhero RPGs. Washbourne talks more about the game in this Q&A.

If you want to learn more about Supers RED, this thread on RPG.net is essential reading. The user who started the thread asks a lot of detailed questions about the game, various people with experience playing it weigh in, and even one of the people who wrote the revised edition gets involved. It’s highly informative reading, probably worth looking at even if you’ve already read the game to further elucidate things.

Supers RED is available in print for a very affordable $15 on DriveThruRPG [if you don’t choose the “premium color” option], and Triumphant is available in PoD form from Lulu.

With Great Power . . .

I have to admit, after reading some of these other games, Smallville in particular, I began to feel less excited about With Great Power6. The game is designed to essentially tell variations on one kind of superhero story, stuff like Spider-Man’s The Master Planner Saga. But, after seeing how Smallville was able to do superhero soap stuff so effectively while also being more open-ended plot-wise, With Great Power began to seem less compelling than it once had.

At the same time, I had to remind myself that almost everything I’d ever heard about With Great Power was in reference to the original 2005 version of the game; the author of the game, Michael S. Miller, rewrote the entire thing from the ground up in 2016.

About The Master Edition This is a completely rewritten and redesigned edition of With Great Power. If you are familiar with the original edition published in 2005, you will find very few specific similarities to that game—no aspects, no suffering, no multiple decks of player cards. It’s a new decade and a completely reimagined game. – With Great Power pg 2

The remade version of With Great Power is “Descended From Monkeydome“. I think this is the only game to have ever been inspired by Monkeydome7, and so what exactly that entails requires explanation.

With Great Power is easily the least traditional game I’ll discuss in this series, with the possible exception of Capes. It essentially provides a structure in which players describe things happening. If you feel that FATE and Cortex have a “writer’s room” feel, With Great Power takes that to a much further extreme.

The first thing the game introduces is the context of Tones. Players roll a red and blue die at the beginning of each Phase [I think . . .]. During a red Phase, strong, passionate emotions are emphasized for player characters. During a blue Phase, responsibility and duty are emphasized.

If those sound very vague and difficult to actually roleplay, I don’t blame you. Thankfully, when the game describes each phase it zeroes in on what each set of behaviors corresponding to a Tone should be like. Phases in With Great Power provide structure to the roleplaying; the Phases include an Adventurous Phase, Personal Phase, Scheming Phase, and Villainous Phase. If both of those aforementioned Tone dice from before roll 3 or less it triggers a Subplot to happen during a Phase. If both dice are tied, the hero is Stymied, and they are expected to lose in the short term.

Gameplay advances when players feel like cool stuff is happening. There’s a nine panel grid sheet called the “Fan Faves” sheet; whenever a player feels like another player made something interesting happen in the story, they write it down in a panel on the grid [the GM can also weigh in]. One panel on the second row must echo something from the first row, and a panel in the third row has to echo something from the first two rows. After all nine panels have been filled, Gloating Mode begins.

During Gloating Mode players, and sometimes the villain, Reincorporate. Everyone looks at Subplots and stuff from the Fan Faves sheet to try and wrap up the story in a satisfying way. The last player who didn’t reincorporate can provide an Epilogue to the story.

It’s worth noting that a single session of With Great Power is meant to tell an entire story, and that sessions are supposed to take 2 – 4 hours. The game is built for one-shots, which isn’t to say that characters cannot return for multiple games.

You might be wondering about how action resolution happens in With Great Power. The answer is that there are no real action resolution mechanics; players just say what happens.

“I just get to say what happens?” Yes. You do. I trust you to describe the next few panels of the imaginary comic book. I trust you to be the best kind of fan of your hero—exulting in their triumphs and sympathizing with their challenges. Your friends trust you, too. They’re waiting to hear what you’re going to add to the story. It may sound like a big responsibility, but you’re not alone. You have the tone that the dice have given you. You have the elements written on your hero sheet. You have everything that has happened before. And you have a lifetime of daydreaming about superheroes. Most of all, you have your friends rooting for you. It will be more than enough. – With Great Power pg 15

I have to admit, I did find some elements of With Great Power a little confusing, as simple as the game is clearly meant to be. The Dice and Tones section is a little vague about certain things; when exactly are dice rolled for Tone? Every Phase, or every Scene? A lot of things make it seem like the answer is Phase, but then other things make it easy to infer the answer is actually Scene.

The answer is in the book, but it’s not under the Dice and Tones heading, but rather the Overview of Gameplay heading a few pages earlier.

As I read the book, it became easier to infer how the game is supposed to be played because of what’s implied by the text. But it still feels like the text is occasionally confusing, and sometimes fails at being a simple reference. To be clear, With Great Power is not a chore to read, it just sometimes feels like it’s not as immediately obvious as a reference material should be.

Gameplay in With Great Power might sound very loose, but there are things that provide structure. For instance, during a Personal Phase someone a hero knows will want something from them that they do not want to give; this isn’t completely free improv.

Character creation in With Great Power is interesting. Players draw five playing cards, with each playing card providing an interesting question to guide the creation of a hero; these could be a useful tool for creating characters in any system. A useful reference sheet is included that will guide any players through character creation; character creation is not just writing flavor text, even if characters don’t have stats.

Ace, ♡ – Your powers mark you as part of a group. Do you hide the connection? What do you think of this group? What does the world think of it? – With Great Power pg 82

The changes between the original With Great Power and the remake seem very extensive, but from everything I’ve read, the remade game looks simpler and a lot more intuitive. At the same time, it does look like a handful of things were lost.

Ron Edwards wrote an entire piece about a particular scratch pad mechanic that didn’t make it over, and while it sounded very cool it would’ve been a bad idea to contrive a reason for it to be in the new version of the game for the sake of it.

The other thing is a bit more sensibility based. There’s a trend in a lot of modern TTRPG stuff away from what could concisely be described as brutality; the most obvious example is PC death becoming increasingly less common in D&D. I also notice that a lot of people seem to view statistically low chances of success as being inherently dated.

You might notice in the quote from the introduction that “suffering” has been removed from With Great Power, and while to some degree that was just the name of a tracker in the original version of the game, it does seem like this new version of the game has less built-in sadism towards the players.

Was the way the original game made players fail a lot during the early going an interesting mechanic, or was it annoying? That’s for you to decide.

I will say that, having listened to the System Mastery episode on the original game, the remade version of the game sounds a lot more replayable. The original game’s intended story shape seemed a lot more rigid, while the shapes of stories in this remake seem a lot more flexible; Phases can happen in any order and repeat if necessary.

I said at the beginning that the game seems to emulate The Master Planner Saga, but this reading of the game is a lot more applicable to the original. If I was reading this remade version in isolation, especially if it had different cover artwork, I probably wouldn’t have arrived at that same conclusion.

The game does include some incredible reference materials detailing what happens during each Phase and Mode that I think will reduce the amount of questions at a given table to a minimum, which is the kind of thing I always love to see. The back of the book contains a bunch of useful tables for creating Villainous Plans and Splash Pages.

With Great Power, quibbles about some unclear rules aside, seems like a solid game. It’s probably a game best appreciated by a group of creatives; there are some people that I think would have a lot of trouble with the lack of traditional action resolution mechanics, and also a lot of people who would probably be completely disinterested in the shared storytelling aspect of the game.

The original version of With Great Power was not a disliked game; it was very positively received in most places. But I don’t think it does this remake any favors that most of the existing press about the game is in reference to something with a completely different set of mechanics; I think if more people knew about how this remade version of the game worked it would be a lot more popular. Its writer’s room approach isn’t going to appeal to everyone, but people who want to tell stories about superheroes with their friends will find a lot to love here.

If you’d like to learn more, Michael S. Miller collected some write-ups that relate specifically to the new edition on his website: Jason D’Angelo [The Daily Apocalypse], Ron Edwards [not the same piece from before], Step Into RPGs.

If you enjoy Sabrina TVBand’s writing, you can read her personal blog, follow her on BlueSky and Letterboxd, view her itch.io page, and/or look at her Linktree.

- I keep capitalizing FATE because it looks cooler. ↩︎

- The math probably doesn’t check out here, but hopefully you get the gist of what I’m suggesting. ↩︎

- For whatever reason, nobody refers to Triumphant Revised and Expanded as Triumphant RED. ↩︎

- Credit to Lowell Francis’s writeup on Supers RED for drawing my attention to this particular post, which I’m now referencing in almost the exact same context. ↩︎

- Technically Mini Six. ↩︎

- There’s an ellipsis in the logo of the game if you look closely. ↩︎

- Something I found funny; Monkeydome is a post-apocalypse game, like Apocalypse World, which birthed the much more prevalent Powered by the Apocalypse. Except Monkeydome seems to be more gonzo. Also, there is another game that uses Monkeydome’s mechanics, Swords Without Master, but it shares an author with the original game so it doesn’t count. ↩︎

Interesting overview… I’d like to check out Supers, and,m as you said:

I’m going to talk about the original version of Supers here, because it only costs a dollar on DriveThruRPG.

Is this still available on DtRPG, though? I found some supplementes/NPC collections but not the actual rules.Maybe I just missed it, could you please provide a direct link, if possible?TIA,Pamar

LikeLike

Here you go https://www.drivethrurpg.com/en/product/105204/supers-the-comic-book-rpg

LikeLike

Thanks a lot!

(Of course I found the link ~47 seconds after posting my question but still… 🙈)

LikeLike