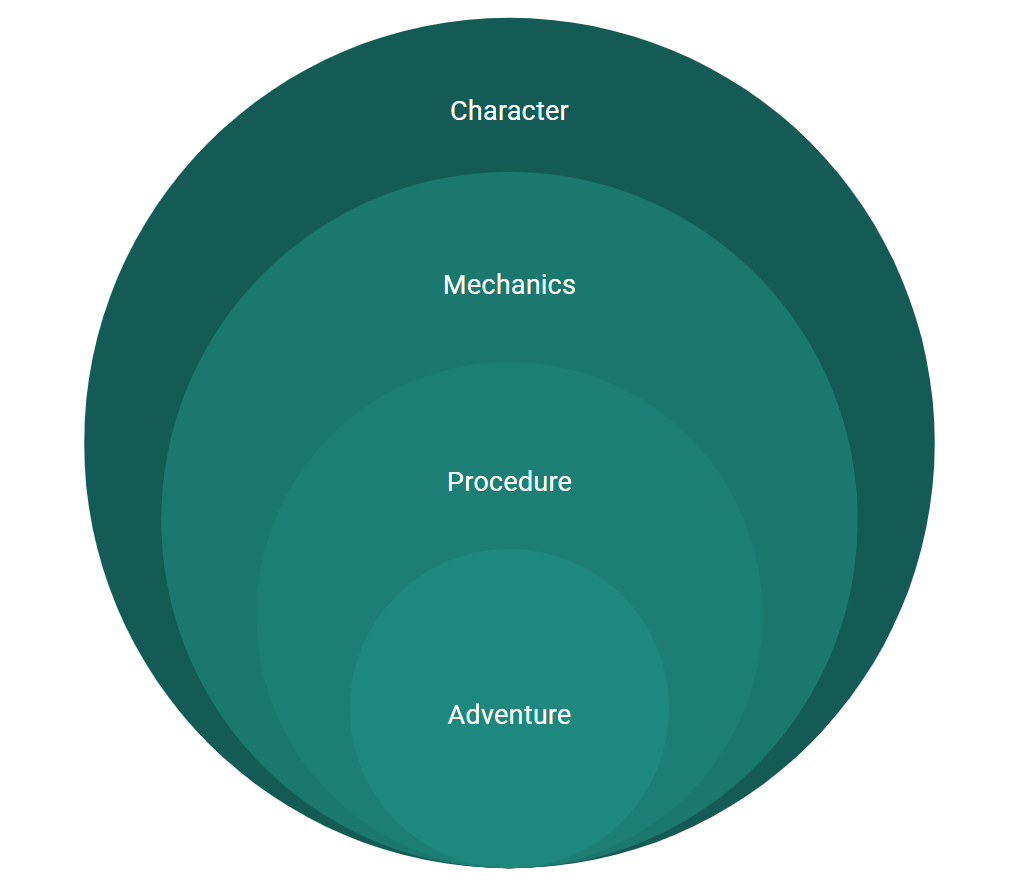

The RPG theory ship sails on unbidden, even as RPG networks of practice seem to be drifting apart. In November, there was a great post over on The Dododecahedron which bucked the trend and pulled theory work from outside of the author’s primary discipline, the OSR. Starting from a description written by Vincent Baker about the PbtA ‘conversation’, Dododecahedron author Rowan describes OSR play as an onion with four concentric layers: Character on the outside, then working inward to Mechanics, Procedures, and finally Adventure. Adventure is in the middle as the diegetic ‘fiction’ that the players are engaging with is the source of truth for OSR play. From there are Procedures, which describe the rules for how to go about play; that is to say, what travel looks like, or when random encounters occur, or how to track consumables. The next layer out is Mechanics, which describe the “rules” as most RPGs understand them; this is where initiative, ability checks, and all those specific bits live. Finally on the outside is Character, where elements like attributes, experience points, and skill ratings, all the things that make characters unique, sit.

This order describes the OSR well. The adventure, be that a pre-written module or not, is considered the core of an OSR game. The reality as prepped in the adventure is what determines the challenges that make up the game, and interacting with that reality is what the game at its core truly is. Rowan does state that ‘a well-written adventure can function as a game in its own right’, and while that’s only true insofar as all participants are familiar with TSR D&D play culture, it still emphasizes that OSR play is perfectly workable without strong engagement with any specific rulesets or particular mechanics. When those alterations are used to narrow the play experience, it tends to be through Procedures; games like Electric Bastionland and Mythic Bastionland build up a specific experience even though the actual Mechanics of the game are neither all that different from those in D&D nor plentiful in an absolute sense.

Having rules and procedures in service to the setting isn’t necessarily unique to the OSR, and Rowan does cite ‘Blorb Principles’ which are more broadly applicable guidelines for running games based on simulationist ‘truth’ as opposed to narrative or game-driven expediency. Putting the character layer on the outside ties the structure together; de-emphasizing character ability is a hallmark of the OSR both in terms of character-specific mechanics and in terms of having the engagement sit with the players as opposed to the characters.

That character layer makes for interesting differentiation. Modern trad is quite character focused; a lot of the play that has evolved since the advent of 5e and Actual Play is what has been called by other commentators ‘OC’ play, with both the descriptive and derisive implications of that term fully intended. This obviously sits on the opposite end of the OSR when it comes to character centricity, but what really makes it messy is that, at a structural level, even modern D&D roughly hews to the same basic onion that The Dododecahedron describes for the OSR. D&D is still D&D, after all.

This discussion of OSR and trad structure got me thinking. Are there games that successfully shift the structure of the onion? Modern trad has different motivations and intentions than the OSR, but the games haven’t necessarily changed in a way that reflects that. If we leave trad, though, there are some interesting counterfactuals that change the order of the onion.

Burning Wheel: Swapping Character and Adventure

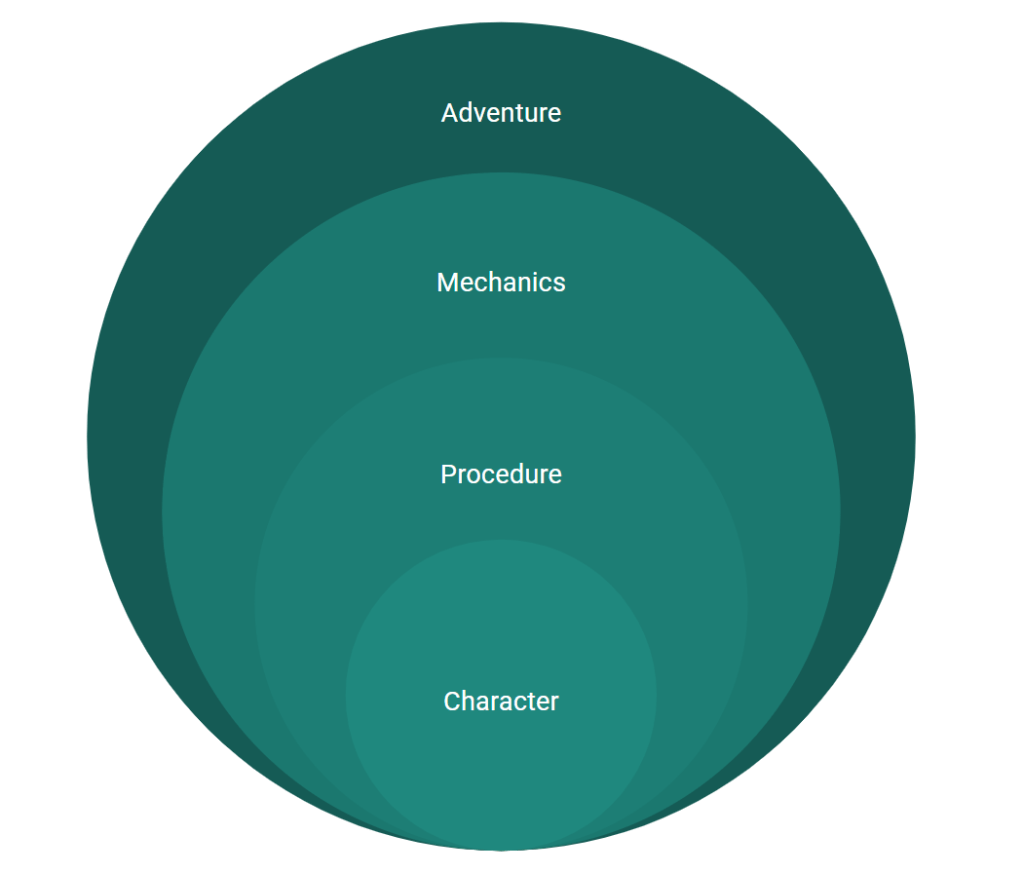

When it comes to long-standing character-focused game designs, Burning Wheel is an obvious choice. The game is driven by characters and their Beliefs, almost to the exclusion of anything else. Given that, you could model the principles of Burning Wheel with an onion by swapping Adventure as the central node of the onion with Character.

Character is everything in Burning Wheel, and it’s key character-specific elements, the Beliefs, which in fact drive the entire game. What allows them to drive the entire game are the Procedures, namely the Artha Wheel and how to employ Beliefs, Instincts, and Traits in a game. Outside of those core elements, Mechanics are used to reinforce character interactions; though some of these Mechanics would be hard to completely omit, a large number of Burning Wheel mechanics are unnecessary so long as the core is being engaged. And finally, on the outside, is Adventure; while the mechanics and descriptive elements of character reinforce the medieval setting, the specific “adventure” is entirely dependent on what the characters are doing, with no diegetic truth being truly necessary for Burning Wheel provided that the characters have Beliefs to strive for and challenges to struggle against.

While Burning Wheel doesn’t really resemble a “trad” game in any appreciable way, the swap of character and adventure does make an implication that the use of bigger procedures mediated by more specific mechanics is the same as it would be in a trad game, and indeed this is one reason why Burning Wheel looks and feels fairly traditional in a way a lot of narrative games don’t. The dependencies are obviously reversed; the setting evolves in service to the characters, and as a result it doesn’t (and can’t) have the same central role in gameplay that established ‘adventure’ has in the OSR.

While it would take more than an onion diagram to generalize Burning Wheel, this illustration does provide a reasonable comparison between Burning Wheel and the OSR when it comes to the game’s priorities. A game driven by creating characters with clear needs and wants first can arrive at this same structure, so long as the game has clear procedures for how to resist these needs and wants to create tension. For all its complexity, Burning Wheel doesn’t actually provide much structure for creating Beliefs (i.e. the needs and wants), rather focusing on giving color to the character so that the player can figure out what they are.

Burning Wheel takes some practice on the part of the GM; as much as the OSR method of keeping everything static and planned may not necessarily be the most common mode of prep for a modern GM, the method of creating everything in service to the characters and their Beliefs is arguably more alien. It can get weirder, though; there is a game where the adventure is literally prepped from the characters’ desires. This diegetic interplay is completely intentional, but could only really exist in a game as particular as DIE.

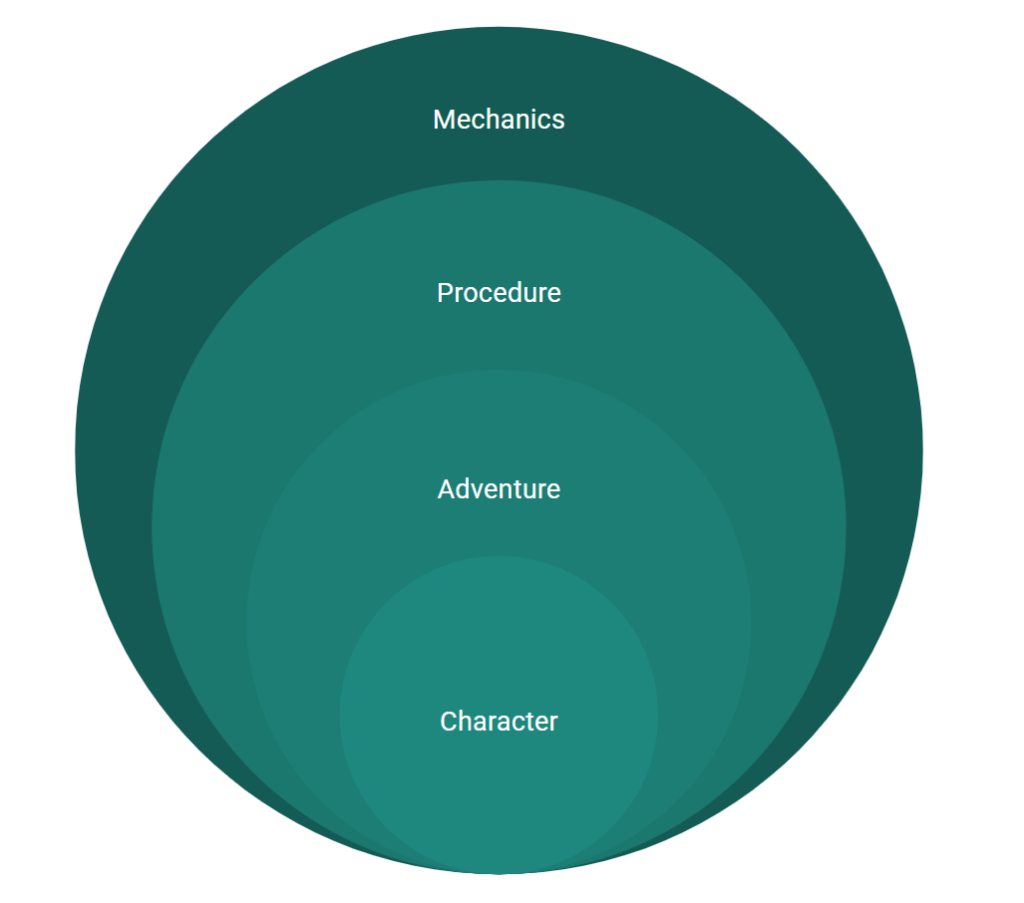

DIE: Character as the core within Adventure

The ‘onion’ of DIE is arguably not replicable; the setting conceit of a world shaped by the desires and traumas of the characters is what makes the game, and what enables DIE the RPG to exist and be compelling even without mirroring all the particulars of DIE the comic. Even if the game isn’t generalizable, it does reflect a different structure to the onion with Character at the middle.

Although character is still in the middle, this structure is different from the one describing Burning Wheel. In Burning Wheel the setting is fairly unimportant beyond what comes directly from the characters (i.e. Circles) and what is informed by the game’s procedures (i.e. Lifepath). In DIE, there is a traditionally prepped adventure that is in communication with the procedures and mechanics much in the same way as the adventure would be in a D&D game. However, the nature of that setting is entirely dependent on the characters. The pre-written DIE scenarios illustrate this perfectly: Whereas a pre-written module for an OSR game is intended to describe the breadth of what the players will engage with, a pre-written scenario for DIE steers the creation of specific characters and then provides setting and encounters which are in communication with how the characters are created. DIE scenarios need to specify what kind of people the characters are because the scenario material will play off of and build off of those specifications.

You could prep many trad games using this version of the onion; arguably this version also aligns to more neo-Trad play as well as to DIE. What makes it work more effectively in DIE, though, is that the world reflects this diegetic reality. An onion with ‘Adventure’ in the middle, like the OSR onion, is one where establishing the setting comes first. An onion with ‘Character’ in the middle means establishing the character comes first, and that setting will be bent and broken in service of the characters. That doesn’t sit well with players who are looking for verisimilitude, it directly implies that narrative truths are more important than setting truths. In the case of something like DIE, though, the character’s truths directly feed into how the world appears, and that itself is an important part of the setting. While a world purporting to be an internally consistent setting may violate suspension of disbelief when it bends to the characters and their story, DIE is a setting literally made from the characters and their story, and meant to be explored as such.

When taking the four elements and the onion structure laid out on The Dododecahedron, shifting the order and putting Character at the middle represents a more profound shift in thinking than most indie games undertake. If you were to look at a game like Apocalypse World, it very well may be described adequately by the original onion as used to describe the OSR. While the setting is established at the beginning of the game through a collaborative process, it doesn’t bend to the characters’ wills; Apocalypse World outright states ‘always say what your prep demands’, which sounds like it could be an OSR principle as well. If we were only talking about gameplay, Apocalypse World would have the same onion as the OSR, but the very different way that the game is prepped and established does make it so that stating that Apocalypse World has ‘adventure’ as a firm and inviolable ‘core of the onion’ is likely not an effective way to talk about its structure, let alone how it compares to the OSR.

DIE and Burning Wheel, though, center characters in pretty radical ways compared to many RPGs, and that can be illustrated with the onion. These are also incidentally games with bright lines between Procedures and Mechanics; Burning Wheel has the Artha Wheel and Beliefs, Instincts, and Traits, which exist more strongly at the table than in enumerated rules, and DIE has persona generation, which happens independent of invoking any of the in-game mechanics at all.

In all of these cases, what makes the game effective at using its structure are how well articulated each of the four elements are. Burning Wheel lives and dies by how players write Beliefs, and as I stated in my review that’s an area where better guidance would make the game significantly more accessible. DIE is much better structured for that sort of accessibility, but it is narrow; even new scenarios require significant adjustment to the procedures of the game. When it comes to the OSR, though, I’m in agreement with the conclusion of The OSR Onion: There are ways to incorporate new systems which support and reinforce a game’s central, internally consistent setting, and these new systems would enable more breadth and less reliance on modules for groups to find their best game. Just as games like DIE and Burning Wheel introduce novel systems around centering character, so too can games in the trad and OSR space encourage play in more and more interesting worlds.

Like what Cannibal Halfling Gaming is doing and want to help us bring games and gamers together? First, you can follow me @levelonewonk.bsky.social for RPG commentary, relevant retweets, and maybe some rambling. You can also find our Discord channel and drop in to chat with our authors and get every new post as it comes out. You can travel to DriveThruRPG through one of our fine and elegantly-crafted links, which generates credit that lets us get more games to work with! Finally, you can support us directly on Patreon, which lets us cover costs, pay our contributors, and save up for projects. Thanks for reading!

2 thoughts on “Coring the Onion: OSR structuralism and non-OSR games”