Here’s a link to Part ,1 in case you missed it. I originally was going to just go straight into talking about the games, but I decided I’d quickly talk about some of my favorite superhero comics here. I’m doing this partially so that you, as a reader, can know what I care about in superhero comics, what I would want to see emulated in a game . . . but it’s mostly so I can create a cool visual motif for this article. You can skip this if you don’t care.

An artist / writer I’ve been enjoying recently is Adam Warren. He’s mostly well known today for Empowered, which I’ve not yet read. I started with the comic that made him famous, The Dirty Pair, which I wrote about extensively for Women Write About Comics. I recently read Iron Man: Hypervelocity and enjoyed that, even if it feels like the first half of a two-part story. I’ve only read about half of his run on Gen¹³, but that’s a very interesting book as well. Warren loves doing stuff about fame / the media and transhumanism, sci-fi stuff with legitimately speculative ideas; he’s a very interesting talent.

Jack Kirby is probably my all-time favorite artist / writer. I’ve read a lot of his stuff, but I think the best Kirby comics are OMAC, Fantastic Four, and his 70s run on Captain America. OMAC was cyberpunk before that was a thing, and if someone told you Fantastic Four was boring vanilla whitebread pablum they were lying through their teeth. 70s Captain America is wild stuff, and it feels a lot less phoned-in than Kirby’s 60s Captain America books, which clearly had lower priority for him than Fantastic Four.

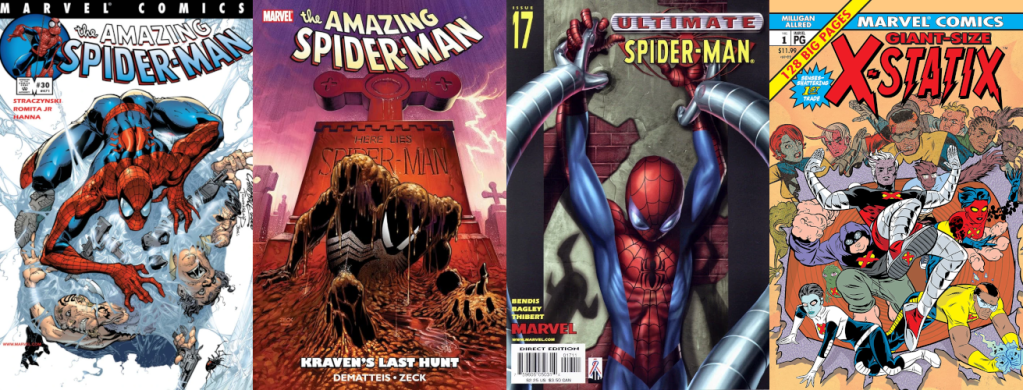

I’m a huge Spider-Man fan. Steve Ditko and Romita Sr made the definitive Spider-Man comics, but J Michael Stracynski’s run on Amazing is also incredible [excluding One More Day, of course]. The issues of JMS’s run illustrated by Romita Jr are the real highlights. Kraven’s Last Hunt, by J. M. DeMatteis and Mike Zeck, is one of the only great Spider-Man “graphic novels”. I also love what I’ve read of Bendis and Bagley’s Ultimate Spider-Man.

Peter Milligan is a comics writer from the “British Invasion” that gets overlooked all the time relative to Grant Morrison, Alan Moore, and Neil Gaiman. X-Statix is a book about a mutant superhero team with its own reality show that features incredible artwork by Mike Allred, and Shade the Changing Man is a book about America that feels possibly more relevant now than it did when it was first being published.

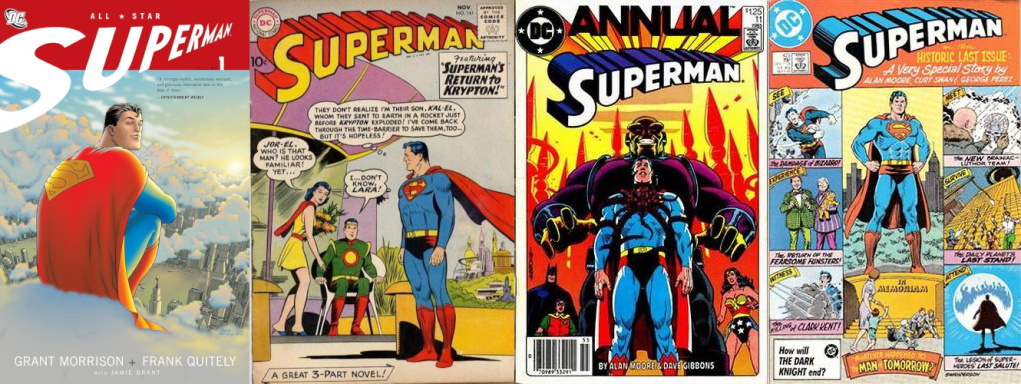

Grant Morrison is great too. Doom Patrol is the best version of Morrison’s entire erudite surrealism thing that I’ve read, illustrated predominantly by Richard Case. JLA, illustrated mostly by Howard Porter, is a book that I remember making my brain feel like it was going to explode as I read it; really captures the scale of the immensely powerful DC characters. Earth 2, a JLA-spinoff drawn by Frank Quitely, is also incredible.

My favorite Morrison comic is probably All-Star Superman, which just might be the all-time best Superman story. There are a lot of incredible Superman stories. Superman’s Return to Krypton, written by Jerry Siegel and illustrated by the legendary Wayne Boring, is a true classic. Alan Moore’s Superman stories, For the Man Who Has Everything and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, are both perfect [art by Dave Gibbons and Curt Swan respectively].

I wouldn’t really consider Daredevil to be one of my favorite superheroes, but he has some great stories. The Man Without Fear has solid writing by Frank Miller, paired with some of Romita Jr’s best art. Born Again, by Miller and Mazzucchelli, is a masterpiece of superhero noir storytelling, and easily one of the best superhero comics ever made. Kevin Smith’s Guardian Devil feels like a loose spiritual sequel to Born Again, and it really makes me wish Smith spent more time writing comics, because it seems to be where his true talents lie.

Since I was just talking about Frank Miller, I should say that The Dark Knight Returns features some of the greatest comics formalism ever; the virtuosity of the book’s 16-panel grids are basically unmatched to this day. RoboCop vs The Terminator, illustrated by Walt Simonson, is less substantial, but still very fun. Barry Windsor-Smith’s Weapon X is a book with some very immersive art / storytelling. I haven’t read as much X-Men stuff as I would’ve liked; back when I wanted to collect the Claremont / Cockrum run, the relevant Marvel Masterworks books were all OOP and very expensive. I loved the first volume, though.

Amanda Conner is easily one of the three or four best working comic artists today. I first became familiar with her work through her Vampirella comics; a lot of Vampirella stuff is a little too heterosexual on a sensibility level for me, but Conner draws the best faces in the comics biz. Conner’s work on Power Girl is essential; her run on the character is some of the best-executed superhero comedy stuff I’ve ever seen. And, once again, she’s so good at drawing faces you might even forget to look at Power Girl’s boobs.

Now it’s time for the weird stuff. A lot of Marvel’s 70s books were pretty shit, but Jim Starlin’s Warlock was a mind-bending “cosmic” book. Omega the Unknown, written by Steve Gerber and Mary Skrenes, and illustrated by Jim Mooney, is a book I remember loving even though I haven’t read it in the better part of 15 years. Scott McCloud’s Zot! was a great sci-fi comic that transitioned into being an even better slice-of-life book [it’s the comic in this article’s featured image].

I realize I didn’t get into “why” I love most of these, but this opening was already an indulgence and there are nearly 10,000 more words in this article.

Games I Haven’t Talked About

Advanced FASERIP

I was such a fan of Blacky the Blackball’s Masks that I decided to give Advanced FASERIP a look, even though I had a feeling I wouldn’t enjoy it nearly as much. Here’s a quick recap: Masks and FASERIP are both retroclones of Marvel Super Heroes, but Masks adds some FATE-isms to the game inspired by Icons, while FASERIP is a more faithful clone that still modernizes some aspects of the original game.

Advanced FASERIP is an iteration on Blacky’s original FASERIP, released just a few months ago on December 18th. This thread on RPG.net outlines many of the changes made, but the gist is that both versions of FASERIP and the original Marvel Super Heroes are highly compatible with one another.

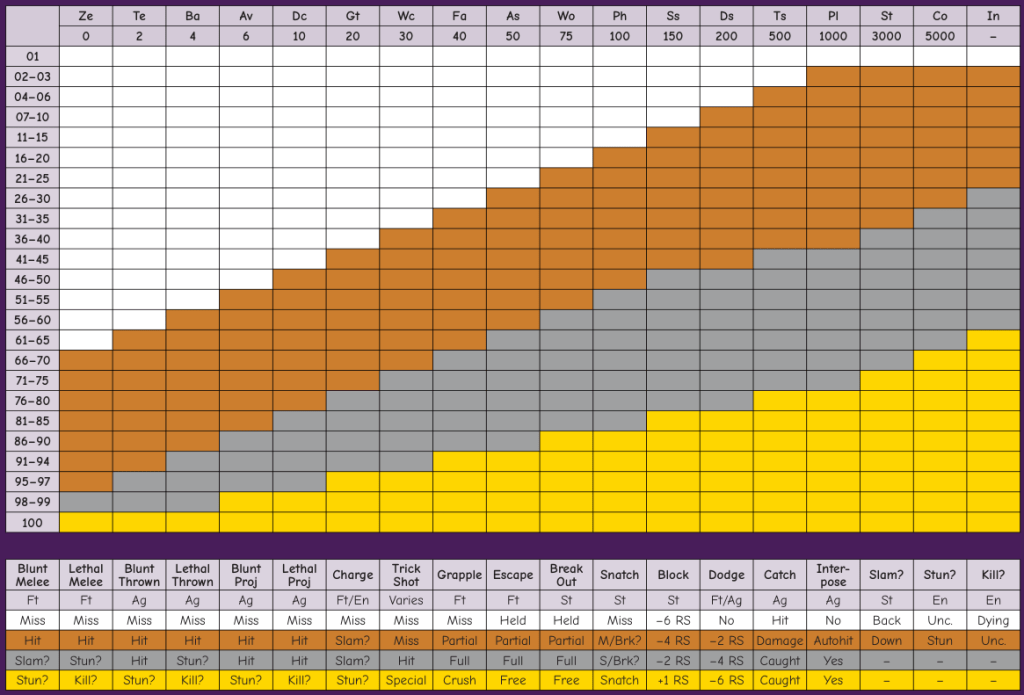

Masks used FUDGE dice, while Advanced FASERIP uses percentile dice, like the original Marvel Super Heroes. Every roll in the game requires players to refer to a large table. A player looks at their relevant rank column, and then sees what probabilities their rank has of failing or succeeding. A lot of games from the 70s and 80s required players to look at tables after completing rolls, and FASERIP has the least offensive table I’ve seen in an RPG of this vintage, mostly because it’s the same table literally every time.

Before we get deeper into the book, it’s random character generation time. Dusky Darktrix used to only be a mild-mannered amateur wrestler, who also used the pseudonym Dusky Darktrix, real name Terry Tenebris. But, after a freak accident involving a gasoline tanker and a nuclear isotope, Terry gained superpowers. She could now turn into a 2D shadow version of herself, phase through objects, and turn into a cloud of gas. She also has the ability to control the emotions of others.

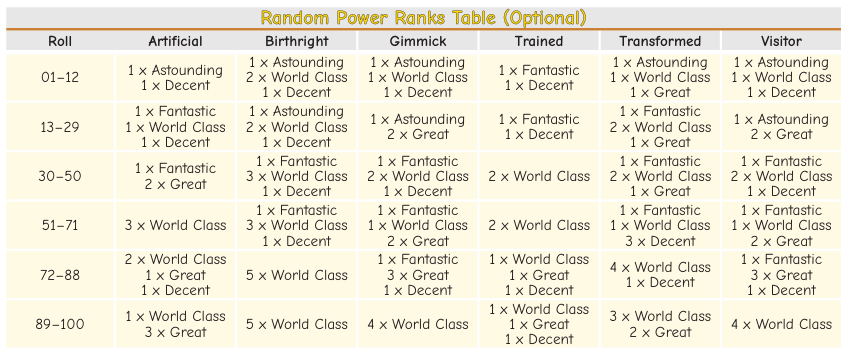

I love Advanced FASERIP’s random character generation; it feels like an iteration on what I experienced in Masks, because it basically is. At nearly every step of character creation players can choose how much randomness they want, and the inclusion of several tables allows players who don’t want to count points to simply roll for how their points will be dispersed amongst their powers or stats.

My only real complaint is that, without Aspects, players have to bring personality and depth to their character themselves. This is normal; most traditional games are like this. But Jinx Joxle, my Masks character, and Dana Doich, the Marvel Heroic character I’ll discuss later, feel like much more vivid characters to me after filling out their sheets than Terry Tenebris. But, otherwise, Advanced FASERIP has the best random superhero generation I’ve seen yet, at least on an ease of use level, given its detail.

Advanced FASERIP has largely easy combat with meaningful depth. Some reference materials will probably be needed for a while, but it’s all stuff that can fit onto a single sheet of paper. The game uses a zone movement system that’s much like FATE’s movement, which is pretty loose and simple.

Unlike Masks, Advanced FASERIP uses the Karma1 system from the original MSH, except rebalanced. Characters gain Karma for saving people, keeping their word, and stopping crimes. They lose Karma for not doing those things, and can lose all of their Karma if they kill someone. Some Karma choices are questionable; a superhero loses Karma for intimidating people, which would be unfair to a character like Batman. Thankfully, the book says that you can make Karma mean whatever you need to in a given campaign.

The original Marvel Super Heroes made players choose between using their Karma to boost rolls or advance their character. Thankfully, Advanced FASERIP manages to fix this. Players simply need to divide a power’s rank value by five [rounding up], and after they’ve boosted that power using Karma that many times, they get to advance it to the next rank. Karma can also be used to turn Stunts into powers, increase wealth, improve fame, etc.

After chapters on base building and stock NPCs [children, cops, ninjas, etc], the book moves into its GM section. It’s not very long, but all of the advice is pretty good, largely focusing on making sure everyone at the table is happy rather than genre emulation, adventure writing, etc. It does include a very rudimentary scenario seed generator.

The book also includes a very detailed section on troupe play, which is basically a rotating GM setup. I thought it would basically just talk about how sometimes members of a super team are busy and not present, but it also includes notes on creating a setting optimized for troupe play, where each player creates multiple PCs, villains, and NPCs, as well as a central organization their heroes work for.

The book then concludes with a list of powers, at the back of the book, where it should be. Advanced FASERIP is a very complete game; Masks felt like it was extremely bare-bones, basically just the mechanics and a list of powers, but Advanced FASERIP benefits from its additions.

Something I dislike about Advanced FASERIP is its visual design. The book uses public domain comic art, mostly from the 30s and 40s. It gives everything a musty feeling, and the contrast between the scanned newsprint and clean white pages looks ugly. The original version of FASERIP used very nice art that was released under a non-commercial license, and so unfortunately Advanced FASERIP steps down in this area.

The book also uses what seems to be comic sans as its main font, which doesn’t bother me. Say whatever hyperbolically critical things you want about comic sans, it is easy to read. But it does bother me that comic sans is also used as a heading font; that’s where I draw the line. The cover of the book is also horrifically ugly.

Otherwise the layout and general design of the book is very clean and sharp; headings are where they should be, tables are clean and legible, and once again Blacky demonstrates his skill at writing clear and easy to understand text. If I ever have another OSR phase I might have to buy a copy of Dark Dungeons X, his Rules Cyclopedia retroclone.

If you’ve been reading this long, you probably already know what I’m going to say about Advanced FASERIP. It’s a very good recreation of one of the most popular traditional superhero games ever, and it’s free. People with a lot of experience with the original Marvel Super Heroes seem to love it. But, despite the quality of Blacky’s text and his various refinements to the original game, I still don’t like it as much as I liked Masks.

I feel a little crazy about liking Masks, because I’d literally never heard anyone mention it before working on Part 1 of this series; it was never that popular to begin with, and it must now have the worst SEO of any RPG ever. Blacky himself doesn’t even seem that fond of it, but I’d love to see a revised edition of Masks that reflects how much Blacky’s retrocloning skills have improved since 2014. I guess I can feel slightly validated knowing that Lowell Francis of Age of Ravens also seems to think Masks is pretty neat.

Marvel Multiverse RPG

I originally had very negative thoughts relating to Marvel Multiverse, because the discourse surrounding the playtest version of the game was highly negative. It didn’t help that its name evokes the multiverse concept, which feels very on-trend in a tacky way. But, I stumbled across some discussion of the game that implied its final edition had improved quite a bit, so I decided to investigate.

This is a game where I didn’t read the core rulebook, so this is basically going to be me talking about what I’ve read about the game.

Marvel Multiverse is the fifth Marvel TTRPG, and it has quite a legacy to live up to. The original Marvel Super Heroes, as I’ve already established, is a very highly regarded game with many retroclones. Marvel SAGA, with its unique card-based mechanics, is more obscure, but it has its fans. Marvel Universe [singular] was an interesting diceless game that had a very short life. Finally there’s Marvel Heroic, perhaps the most highly regarded Marvel RPG in modern game design circles; I’m going to spend nearly 2,000 words discussing it later in this article.

It’s maybe worth mentioning that Marvel Universe was self-published by Marvel, and was allegedly discontinued after about a year because it wasn’t selling D&D numbers. Marvel Multiverse, Marvel’s second self-published RPG, hopefully doesn’t suffer the same fate.

As you may have noticed, basically every Marvel RPG aside from MSH has something that makes it a bit weird. Card based mechanics, a diceless pip system, the Cortex Plus system; even MSH has its iconic universal table. From what I’ve read, Marvel Mutiverse is a very firm return to traditional game design. No metacurrencies, no Dramatic Editing, no Aspects, etc.

Multiverse uses a 3d6 system, called the 616 system, where one of the dice is basically like the Ghost Die from Ghostbusters, except instead of always causing something bad to happen it always causes something good to happen, even if a roll fails. Also unlike the Ghost Die, which had a ghost symbol instead of a 6, the Marvel Die replaces the 1, so it’s kind of like having three sixes across the three dice, plus something even better than a six; very favorable odds. The game also uses a skill-tree system, which seems like an effort to appeal to videogamers.

The playtest version of Marvel Multiverse had 20 different ranks2, which apparently caused some ridiculous math to happen at the table. The final version of the game, thankfully, has only six ranks. Results from the Marvel Die are multiplied against rank, which is very Maid-y.

Whenever I read about this game it seems like there really isn’t much to discuss; I often hear people say that it’s only mechanically meant for superhero fighting and not much else. This exchange from an official Reddit AMA makes it sound like basically everything boils down to the GM fitting it into the game, rather than there being mechanical reinforcement for things like rescuing civilians. A lot of games have mechanics that allow weaker characters to keep up with stronger ones [e.g. giving weaker heroes extra metacurrency points], but it sounds like Marvel Multiverse doesn’t even do this.

Dionysos and Rob Wieland in an RPG.net thread basically reached the same conclusion about the game; it’s a highly traditional game that’s not meant to challenge anyone’s preconceptions about what an RPG is and how they can work. It’s a game made for people who’ve seen characters playing D&D on Community or Big Bang Theory. Probably a good business move for Marvel, but I don’t see this going down in history as one of the more highly regarded Marvel RPGs. Popular? Maybe.

The thing that might really help Multiverse is supplemental material. I imagine the upcoming Spider-Verse and X-Men expansions will be very popular, and, interestingly, an upcoming one-shot adventure about Deadpool will be written by comics writer Cullen Bunn. If Marvel Multiverse manages to bring comicbook star-power to its line in a big way, I could see it attracting a new audience of comics fans who don’t play TTRPGs. Although I do suspect that these writers used to writing in a static medium are going to write very railroad-y adventures.

This is a bit more esoteric, but I don’t think this game is going to have a great “flavor” across its product line. Since Marvel was purchased by Disney the quality of the comics, on the whole, have declined; this is the most reviled era of Spider-Man since The Clone Saga, and Marvel editorial’s recent soft continuity reset for X-Men is also disliked. It feels like the comics are meant to be an idea mill for Marvel’s film division now, and / or act as promotion for the movies. The comics are also incredibly sanitized on a content level relative to DC’s offerings. This just doesn’t feel like a great era for a licensed Marvel RPG to emerge into.

I haven’t read anything about Marvel Multiverse that suggests it’s anything special; if this game wasn’t based on a highly lucrative IP I don’t think it would’ve made any kind of impression. Multiverse’s core action resolution mechanics sound kind of fun, but that’s probably because they make me think of Ghostbusters and Maid RPG. This is very anecdotal, but I’m surprised by how much I haven’t been hearing about this game on /r/RPG.

It’s entirely possible that Multiverse is doing numbers with people who don’t hang out in TTRPG spaces. I think the reason I’m not hearing much about it is because there are so many well-known superhero games, many of which I’m talking about in this series, that it’s hard for something like Marvel Multiverse to make a huge splash with the core TTRPG crowd. Whereas Multiverse is probably only competing for shelf space in Barnes & Noble stores with D&D and Pathfinder products. I guess we’ll discover how it’s really doing in August; will it continue, or will it be the third Marvel game to die in roughly a year?

Marvel Multiverse isn’t available in PDF form, and there are no plans to release it in that format, which feels like a classic instance of a company thinking they have a product so desirable and special that they don’t have to meet the market where it’s at [See: Cortex Prime and its website that I don’t trust].

Additional Reading: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Heroes Unlimited

Heroes Unlimited is a bad game. It uses a system heavily derived from old D&D, which is not good for the purposes of superheroing, and the layout and organization of the book is complete trash. I’m not going to suggest that it’s completely meritless, but there’s no conceivable area in which Heroes Unlimited scores highly.

Except, perhaps, random character generation [and also artwork]. So, I decided to create a character. Two, in fact, because there’s a ridiculous number of options here. Heroes Unlimited has no official character sheet, but if you want an idea of how needlessly complicated this system is, you can look at this unofficial one. The characters I’m going to create below might look like finished characters, but there are a variety of percentages and such that I didn’t even bother messing with. I also didn’t mess with education stuff, because I don’t care to sift through options like Radio: Basic, Wilderness Survival, and Computer Programming.

If it wasn’t for the somewhat involved process of adding up skill percentages and combat bonuses, you could generate a basic character in 10 minutes. – Andrew

The first Heroes Unlimited character I created is Conflagtrix, real name Xæ Xo. The child of ineffectual hippie parents, Xæ Xo became deeply cynical, which was exacerbated by her getting into an accident that gave her fire powers [the very same accident that gave Dusky Darktrix her powers!]. The thing that prevented her from becoming the supervillain is the knowledge that, if she plays her cards right, she can make money as a hero-for-hire without having to worry about the legal complications of villainy. Unfortunately, in order to maintain her secret identity, she does have to do a fair amount of money laundering so she can do her taxes.

Conflagtrix

Secret Identity: Xæ Xo

Alignment: Unprincipled (selfish)

Hit Points: 18

Base Mutant SDC: 30 (+40 from Flight: Wingless)

Education Level: Four years of college (select three skill programs +20% and ten secondary skills)

-Third Born

-Mean, suspicious, vengeful

-Powers manifested late teens

Intelligence Quotient: 11

Mental Endurance: 11

Mental Affinity: 10

Physical Strength: 11

Physical Prowess: 14

Physical Endurance: 15

Physical Beauty: 11

Speed: 22

Power Category: Mutants

Cause of Mutation: Accidental encounter with “strange stuff”.

-No unusual physical traits

Five minor super abilities only (no Major powers)

-Power channeling [the character creates a kinetic surge when they attack with bare hands or feet]

-Flight: Wingless

-Impervious to fire and heat

-Supervision: ultraviolet and infrared

-Energy Expulsion: Fire

You might be wondering about that 22 Speed, and it’s because if you roll 16 or more on your 3d6 roll, you roll an extra exploding 1d6.

In the past, the Mega-Hero was not included among the superbeings of Heroes Unlimited™. The reason: I wanted this to be a thinking man’s game. – Kevin Siembieda, Heroes Unlimited pg 178

The second character I created is Nu Goddess. I didn’t like the numbers I rolled for Conflagtrix, so I decided to roll 4d6 drop the lowest for Nu Goddess [Yes, I do realize I’m never going to play this game]. My rolls were still shitty.

Nu Goddess, real name Nail’Ith Noor, is an alien who came to Earth in search of fame and fortune. She’s almost completely indestructible, not only being nigh-invulnerable, but also having a healing factor. In addition to her immense durability, she can fly and shoot energy from her arms. She has “some” familiarity with Earth, which, according to Heroes Unlimited, means she knows how to speak, read, and write three Earth languages at 90% proficiency.

Nu Goddess

Secret Identity: Nail’Ith Noor

Anarchist (Selfish) Alignment

Hit Points: 14 (+160 Invulnerability) (+13 Healing Factor)

SDC: [couldn’t find base Alien SDC] (+110 Invulnerability) (+25 Healing Factor) (+100 High Gravity) (+40 from Flight: Wingless)

Intelligence Quotient: 12

Mental Endurance: 13

Mental Affinity: 14

Physical Strength: 15

Physical Prowess: 13 (+4 Invulnerability) (+6 High Gravity)

Physical Endurance: 12 (+5 Invulnerability) (+6 Healing Factor)

Physical Beauty: 12

Speed: 9 (x3 High Gravity; 27)

Height: 5’ 6”

Human-like

Reason for coming to Earth: Glory hound

Some familiarity with Earth

Neurosis: Hysterical blindness

Psychosis: Jekyll and Hyde

High gravity homeworld

Power Category: Alien

One Major Super Ability and three Minor abilities

-Invulnerability

-Flight: Wingless

-Energy Expulsion: Energy

-Healing Factor

For Nu Goddess I decided to roll on the Insanity tables. Yes, Heroes Unlimited allows players to roll “insane” heroes. This might surprise you, but there are some things in the Insanity section that might be in poor taste. This chapter includes notes on alcoholism and drug addiction, multiple personalities, affective disorders, and much more. I’m going to be honest, some of this is kind of fun; a hero can mistakenly believe that their powers only work after they’ve eaten a certain kind of food, “The Popeye Syndrome”; the book includes a d100 table suggesting possible foods.

I rolled two fairly benign things; hysterical blindness and Jekyll and Hyde syndrome. Nu Goddess goes blind when she’s very stressed, but I’m honestly not sure how stressed someone who’s basically indestructible can get in a combat situation.

If you want to hear more about Heroes Unlimited character creation, the guys from the System Mastery podcast guested on the Character Creation podcast and did three entire episodes about it, totaling at nearly five hours in length.

Additional Reading: 1, 2, 3, 4

Going Deeper Into Games From the Original Article

Marvel Heroic Roleplaying

I originally wasn’t planning on covering Marvel Heroic Roleplaying for this second part, but after enjoying reading Smallville so much, I decided it was worth taking the deep dive with Heroic Roleplaying. The big conceptual difference between the two games, aside from company affiliation, is that Heroic Roleplaying is a superhero team game rather than a superhero soap simulator. While this game is designed for use with the Marvel universe, it can be used as a generic supers system fairly easily.

Marvel Heroic Roleplaying opens with a foreword from Jeff Grubb, co-designer of Marvel Super Heroes; I can’t think of a better endorsement than that. The book then breaks down what a character sheet looks like before moving into basic action resolution stuff.

Marvel Heroic Roleplaying, as you might expect, shares a lot of similarities with Smallville. But, true to Cortex’s reputation for being highly modular and tweakable, there are many differences and distinctions.

The kinds of things on a Marvel Heroic character sheet that receive die values are different than the ones on a Smallville sheet. Marvel Heroic characters don’t have Relationships like Smallville characters do; instead they have different die values for when they’re working alone, with one other person, or with a full team. But the general principle, that characters have different die values for different things rather than traditional stats, is basically the same.

Action resolution in Marvel Heroic, at its core, is also similar. Players create a die pool with all of their relevant dice, roll them, choose the two highest results, and then add them to get their final number. Unlike Smallville, characters also get an effect die, which determines the effectiveness of what they did. I know, that’s confusing, because what the hell was that other number we just rolled, but effects are usually something similar to creating Advantages in FATE.

Marvel Heroic uses Plot Points as its player metacurrency, and these points are used for a variety of different things, mainly adding extra dice to the dice pool in different ways. Players can usually earn Plot Points by allowing bad things to happen to themselves in a way similar to FATE3 Aspects, but more interestingly, the GM gives players Plot Points when they “activate an opportunity”. When a player rolls a 1, the GM can choose to take that die and add it to a Doom Pool.

The GM can also add dice to their Doom Pool by having villains do shitty things that don’t involve creating Complications or giving player characters Stress; an example included in the book is a villain antagonizing civilians. The opportunity cost here is that they weren’t attacking the heroes instead, but of course creating emergencies has other tactical advantages.

There are 10 different things the GM can spend Doom dice on, ranging from adding dice to a roll, splitting up a team of heroes, to changing the initiative order. The Doom Pool is also rolled in its entirety for certain opposed roles, although players do get experience points if the GM rolls any D12s. A lot of this stuff sounds overpowered, almost antagonistic, but the GM should feel confident playing rough because every die in their pool required them to give the players a Plot Point.

This kind of tit-for-tat metacurrency exchange is basically the foundation of Marvel Heroic. A lot of games with metacurrencies have GM advice along the lines of “If a player completely runs out of X currency, make sure you give them more fast”. In Marvel Heroic, the exchange of points is engineered in a way that’s extremely fluid, constant, and automatic. There’s more stuff I haven’t mentioned about how this all works, like how the GM can increase the size of the die they add to the Doom Pool if the player rolls multiple 1s, but everything I’ve described covers the basics.

Earlier I mentioned that characters have different die values depending on if they’re working alone, with one other hero, or with a full team. This is an interesting mechanic, because it provides a mechanical reason for characters to not always operate as a full team. Spider-Man works great with a buddy, and Daredevil’s second highest die value is his buddy die, so they might split off from the larger group and complete tasks together.

That’s a really nice thing to have in a superhero RPG. Marvel Heroic does everything it can to mechanically add genre reinforcement to the game, but only really for the costumed side of things. The book does specifically say that scenes where characters just talk to each other should be placed between action scenes, but I was hoping for a little more in that area.

Something divisive about Marvel Heroic was its character creation. Creating a new character sheet in Marvel Heroic can only be described as being “vibes based” if you use the procedures outlined in the core rulebook. Essentially you pick a pre-existing hero, write down their powers, limits, etc, providing die values that seem appropriate . . . and that’s basically the gist of it. It’s extremely loose. It doesn’t help that the lists of powers and specialties are surprisingly brief. There are literally 20 powers, including an example set tailored specifically to Beast. Granted, many of those powers encompass multiple powers [e.g. size-changing includes growing and shrinking], but I think this is the shortest list I’ve ever seen in a game that does include a dedicated list.

It’s not that people can’t think of powers themselves, but nobody wants to create an accidentally broken character, and conversely, nobody wants to accidentally create a character who’s too weak. It’s also worth mentioning that the list of powers is not just a literal list, but it also says how effective each die size is for each power [e.g. describing roughly how tall d8 of Growth is]. At least with Smallville character creation was done with the whole table, and there was a highly detailed procedure to help players.

Margaret Weis Productions eventually released a free PDF outlining how to randomly create a Marvel Heroic character4. It took some digging, but I managed to find the PDF and create a character. I have mixed feelings about Heroic’s random character generator; the character I ended up creating is pretty neat, but the amount of options in character creation feel extremely limited. I was rolling in the Uncommon Powers subtable, for instance, and ended up rolling 6 out of 10 possible options.

I prefer the philosophy of rolling from a list of every possible power and re-rolling if something doesn’t make sense to having certain options grouped together so that it’s less likely players will feel compelled to re-roll. Not only because I’m perfectly capable of deciding if my powers work together or not, but also because a lot of super people have a list of powers that you could never roll together in a system that tries to make things “make sense”.

Rogue having super strength, flight, and the ability to steal people’s powers and memories is a weird combination. Doctor Doom is both highly skilled with magic and technology, and usually there would be a division between those two things. Spider-Man has super strength, can crawl on walls, use situational precognition, and shoot webs [using what’s called a “gimmick” or “gadget”, depending on the system]; Spider-Man is the kind of character who feels like his powers came from a random list, Superman even more so.

I guess this lack of options can be attributed to this aforementioned PDF being a free giveaway for people who were disappointed there was no random character generation; it probably wasn’t worth the effort to make a more expansive list of possibilities because of how detailed certain SFX and Limits can be, for instance.

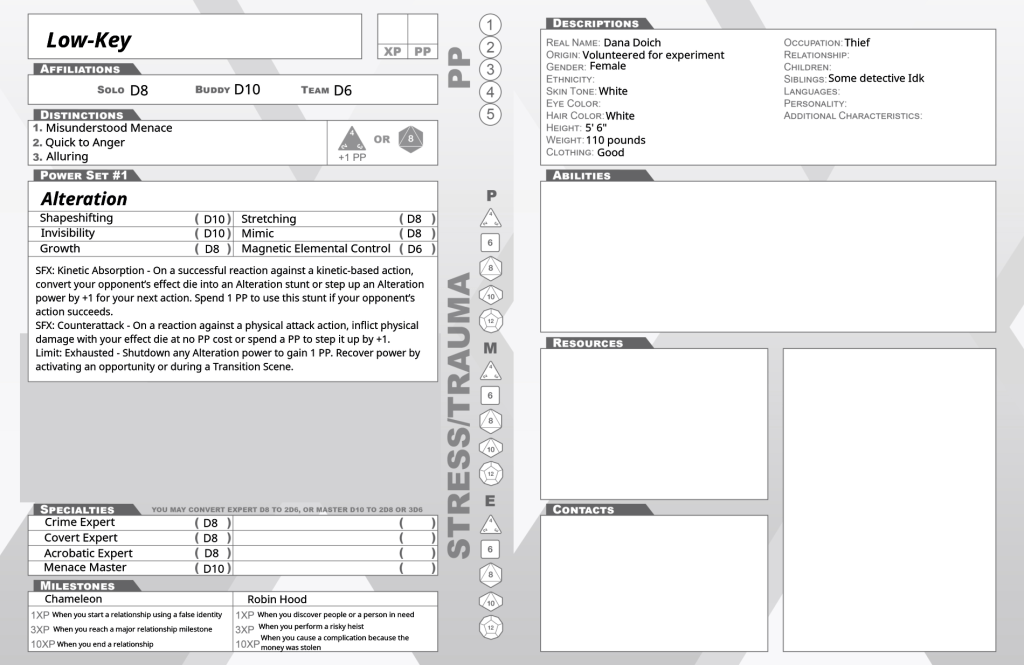

Here’s the character I created. Her super name is Low-Key, and her secret identity is Dana Doich. She’s an anti-hero thief who steals stuff from rich scumbags. She can shapeshift into different people on a cellular level, turn invisible, stretch, mimic powers from other supers, and grow up to 15 feet tall. She also has some control over magnetism, which is useful for picking locks and opening safes. She’s also something of a compulsive liar [Get it? Low-Key, Loki?].

You might be wondering what the Milestones are at the bottom of the character sheet. They’re basically objectives a character has to complete to gain XP. For Kitty Pryde Milestones can relate to starting [and ending] a romantic relationship with another hero. For Captain America, Milestones can involve convincing other heroes to join The Avengers. It’s difficult to create Milestones for a fresh new character, because you need to know their personality and goals. It’s kind of like thinking of FATE Aspects, except they need to fit a more specific format. The book recommends altering Milestones from the pre-existing character sheets in the back of the book.

Milestones are an ingenious way to guide player character behaviors, and I’d like to see more games do stuff like this. Except it might be useful to provide a large, generic list of Milestones purpose-built to be tailored.

I do agree that making characters in Marvel Heroic is a bit exhausting, but in the end, I had a new character that I felt I really understood, much like my Aspected Masks character, Jinx Joxle. And, I must concede, it’s exhausting because I didn’t relax when I created my character like the book advised me to; “balance” is something the game tells players to not worry about.

Something interesting about Marvel Heroic Roleplaying were its sales strategies. Other books in the product line, like Civil War, also included the “Operations Manual” portion of the core rulebook in full, even using the same page number scheme [“OM46” was the same across all books], which meant different players could own different books and still be able to reference rules together. The core rulebook cost only $20, which remains extremely cheap for a core rulebook printed in color. The book’s dimensions are roughly 6.5”~ x 10.5”~, which is around the size of an average comics trade. This meant it could be sold in comicbook stores, or even in regular book stores, right next to the comicbooks it was designed to emulate5.

Maybe that’s not as revolutionary as I’m thinking it is, since TTRPGs have long been sold in comicbook stores. But it’s an interesting design choice for a book to adopt, and that just makes Heroic Roleplaying’s infamous demise all the more tragic; Margaret Weis Productions dropped the Marvel license after about a year because it was too expensive.

I have to admit, I’m not as wild about Marvel Heroic as I am about Smallville. Smallville’s implementation of Cortex Plus is very simple, the Pathways System is interesting, and its focus is unique. It feels more mechanically streamlined and elegant than Marvel Heroic. Marvel Heroic operates in the much more crowded “superhero team” field, which describes at least 95% of superhero games.

That doesn’t mean that I dislike Marvel Heroic. The game has solid mechanics, and both the GM and the players get to shape the narrative in a big way. But something about it doesn’t click for me. I think my initial impression is that it seems like there are too many choices relating to Plot Points and the Doom Pool for players and the GM to take into account at any given moment, but I have a feeling that’s an impression that reflects a lack of actual gameplay experience. I imagine that, after two or three sessions, everyone at the table will have memorized their options, no longer requiring reference materials. I do want to try Marvel Heroic, and I want to experience its gameplay when it’s firing on all cylinders.

If you want something with a kind of macro-level game design mission statement similar to a FATE superheroes game, but with different mechanics, Marvel Heroic is worth investigating.

Truth & Justice

Truth & Justice was the game from the original piece that interested me the most. This excerpt from the introduction pretty much explains why in a nutshell:

However, I think that the story‐based aspects of the genre are often overlooked when translating amazing superhero action to gaming; the wargame‐based inheritance of RPGs sometimes interferes with the vital characteristics of superhero stories. These characteristics include: the ability of dedicated, highly‐trained but unpowered heroes to work successfully alongside or against individuals with superpowers; the heroism in transcending limitations and overcoming obstacles; the importance of a heroʹs motivations, personal ties, and behavior alongside their more‐than‐human talents; and the sense of freewheeling imagination and improvisation that suffuses the source material. Truth & Justice (T&J) is my stab at encouraging gaming that supports and enhances those qualities. – T&J pg iv

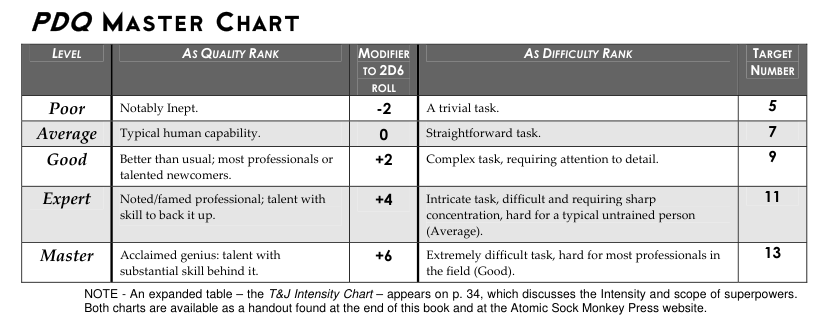

If you’re unfamiliar with Chad Underkoffler’s work, Truth & Justice uses his usual PDQ system. PDQ has an ethos similar to Risus and FATE, but it’s more detailed than Risus and more traditional than FATE. The version of PDQ used in Truth & Justice is often described as being the “crunchiest” version of the system, which is accurate, but that makes the game sound crunchier than it is.

If you’re unfamiliar with PDQ, here’s the lowdown. It’s a system where everyone rolls 2d6 for action resolution, except your rolls might sometimes be modified by Qualities, which are kind of like Risus cliches or FATE Aspects [also FATE Skills]. Specific examples of Qualities included in Truth & Justice include Prankster, Martial Artist, and Charmingly Effusive. Qualities can be good or bad; someone can be an Expert [+4], for instance, or they can have a negative Poor [-2] modifier. Someone who is a Poor Martial Artist will always receive a -2 modifier to their rolls when trying to do things related to martial arts, while a Master [+6] Martial Artist won’t even need to roll most of the time.

If you’re sufficiently good at doing something you don’t need to roll to do it, which is true of most games, but in PDQ that’s codified in a very clear way that makes things unambiguous. Unless you have a dysfunctional group, you’ll never have to debate with your GM about whether or not your character is sufficiently strong enough in the fiction to be able to do something without needing to roll; it’s all there in the action resolution table.

In Truth & Justice, Powers are separate from Qualities, but they basically work the same way; you can have Expert Freeze Breath [+4]. Stunts, creative applications of Powers or Qualities, can be built off of Powers of any level, or Master [+6] Qualities. Stunts, by default, are two ranks below the thing they’re based off of [e.g. a stunt built off of an Expert [+4] Power will be Average [+0] by default, unless Hero Points are spent].

This is all extremely simple stuff; PDQ is a very clean, elegant system. In many ways this isn’t too dissimilar to Risus philosophically, and there are a lot of RPGs with things similar to PDQ Qualities. But PDQ has a much more traditional style of gameplay than something like FATE, while still having more narrative qualities than something like Advanced FASERIP. Truth & Justice occupies a very specific space on the spectrum between traditional and non-traditional games in the superhero genre.

There’s much more to Truth & Justice than what I just described; the book is roughly 125 pages long. Much like other Underkoffler games like Swashbucklers of the 7 Skies and Zorcerer of Zo, he really digs into the conventions of the genre in question. The first chapter of the book is a 14 page long section called The Superhero Genre. It talks about the moral viewpoint expressed in most traditional superhero comics, concepts of scale and the uncanny, and different styles and tones from the genre’s history. The chapter ends with a list of tropes that appear in most superhero comics; nothing mechanical is outlined here, but for certain things, such as sidekicks and time travel, page numbers are included for where the book does mechanically describe how they work.

The [Comics] Code prohibited a large proportion of the violence, sexuality, corruption, and gore found in comics, cutting the legs out from under the horror and crime comics of the time, and further shifting the spirit of comic books away from their pulp roots. This created an artificial world, where good must always triumph over evil and no authority figure could ever be shown in a negative light. This sort of absolutism increased the level of melodrama in comics, but barred many mimetic depictions of the environment. Unable to focus on the social realities, comics turned inward, looking for psychological realities that could be portrayed under this regime: in a word, myth. – T&J pg 8

This chapter on superhero genre conventions is the best of its kind that I’ve seen in a superhero game. Many games don’t have them at all, and others include them in a very perfunctory way. I challenge you to find an RPG book that describes the silver age with as much insight as the preceding paragraph6.

The second chapter outlines the PDQ stuff I was talking about earlier, but with stuff added specifically for T&J. Hero Points are what they sound like; points earned for acting heroically, and also for being affected by Vulnerabilities or allowing Revoltin’ Developments to happen.

In T&J, damage is taken by “downshifting” Qualities and Powers, which is very Risus. The player chooses which Qualities are lowered, so if they want to win a fight they might elect to lower their Family Man Quality instead of their Martial Arts Quality. There’s a procedure in T&J that the first Quality a player chooses to lower should create a new Story Hook related to it [alternately, the GM can choose the Quality that causes the player to “Zero Out”]. Rob Donoghue described Truth & Justice as being a game where someone can “punch Spider-Man in the girlfriend”.

Chapter 3 outlines character creation, which works the way it usually does in PDQ aside from a handful of T&J-specific embellishments like Motivations, Powers, and Stunts.

The next chapter is titled Superpowers, and it has a part of Truth & Justice that I’m not entirely fond of, but can concede is necessary. The PDQ system uses an iconic action resolution table, but the problem is that this table only really works for a “competent normal human being” scale. Vox and Swashbucklers of the 7 Skies7 extended the action resolution table to include difficulties higher than 13, which made sense, because those games allowed players to roll extra dice using metacurrencies.

What Truth & Justice does to account for extraordinary abilities is include a second action resolution table outlining what different levels / target numbers mean in relation to things like super strength, super speed, etc [e.g. A character with “Expert” super strength can lift 75 tons].

I’m not the biggest fan of this, because it basically means folding two tables over each other. I like Risus’s philosophy of including target numbers that extend past the regular action resolution table for superheroes, but I guess I have to concede that T&J’s solution doesn’t require changing anything fundamental about how PDQ works; Risus uses dice pools and PDQ doesn’t. I’m not trying to imply not changing the system is valid because it’s easy; it’s good because it means not having to change how rolling dice works in the system to create a new kludge-y thing that might end up being worse or more confusing. But the limited range of these tables does cause a problem relating to power levels I’ll discuss more later.

The book includes a brief list of powers here, which isn’t really a big deal because of how easy creating powers in PDQ is. Some of the powers seem to be here because they’re highly common, but others seem to be included because they raise questions and the book seeks to adjudicate [e.g. immortality, precognition, luck control, Quality theft, etc]. The book includes some notes on what it calls “Meta-Powers”, which are basically multiple powers included under a single Power. One example it includes is flying being included with weather control, even though it technically is not related. Another example involves an alien being analogous to a Kryptonian. The chapter closes with more information on Stunts.

After a chapter detailing combat the book moves onto its GM section. This contains many things that someone GMing a superhero game should consider, like the superhero community in a given setting and trophy rooms [and trophies, as in things stolen from villains]. The chapter then has some good advice on writing adventures. Something I really love here is the conceit that every session could take place in a different player character’s comic, and that “issue” would focus on their character in particular and they might even have special bonuses. This chapter also includes some great observations about how villains act in superhero stories.

The chapter concludes with some stuff that mostly applies to RPGs in general [e.g. avoid railroading], as well as a few PDQ specific things. Also, nine example NPCs.

After the GM section the game includes three different settings; Second-String Supers, SuperCorps, and Fanfare for the Amplified Man. All of these settings include NPCs, notes on what the public knows, and notes on running the settings. Second-String Supers includes “possible episodes” and SuperCorps includes an entire intro scenario.

I have to admit, I would probably never use any of these settings as-is. But I’d definitely consider borrowing NPCs and stealing ideas from them, which is how I generally feel about good splatbook-type stuff.

The penultimate chapter is a fun bibliography where Underkoffler shares his favorite superhero media from a variety of different mediums. It’s fun to read his thoughts on various comics and movies, even if he says some embarrassing shit; Batman Begins is a better film than Batman Returns and Batman Forever? Deeply unserious. There are also some RPGs listed here, some of which have nothing to do with superheroes, with Risus, FATE, Castle Falkenstein, Marvel Super Heroes, Over the Edge, and an obscure universal system called Storyboard being listed as influences on PDQ and / or Truth & Justice specifically [amongst a few others].

The book ends with some tables for random character generation. It’s worth noting that it would be impossible, or perhaps against the principles of PDQ, to include a “true” random character generator that creates a usable end result. So the tables instead just provide some prompts for creating a character. Here’s what I rolled:

Personality: Flirty

Occupation: Electrician

Hobby: Musician / Garageband

Origin: Act of Generosity

Powers: Transmutation

I decided I didn’t want to create a character with transmutation as their main power, and I also noticed that, in the list of powers, transmutation is listed as transformation; a mild editing mistake. Anyways, here’s what I put together8:

Carrie Crackle used to be a regular electrician until she witnessed a criminal-turned-legitimate-businessman doing something illegal. She was attacked while doing electrical work when he decided to tie off some loose ends, and in the process she gained her powers. Now, she vows to help others who are being affected by those so wealthy they are untouchable by the system.

Electricia

Secret Identity: Carrie Crackle

Motivation: Help people being fucked over by the rich

Hero Point Pool: 5 / 10

Expert [+4] Electrician

Good [+2] Reporter Girlfriend at [newspaper here]

Good [+2] Rhythm Guitarist

Good [+2] Flirt

Poor [-2] Liar

Good [+2] Electricity Manipulation

Good [+2] Duplication

Average [+0] Electrical Phasing

Average [+0] Invisibility

Spin-off Stunt: Electrical Teleportation (Average [+0] Electrical Phasing)

Signature Stunt: Sneak Shock (Average [+0] Invisibility)

I enjoy PDQ character creation; it’s extremely simple, on both an intuitive and mechanical level, but also one is left with a character that still feels meaningful and unique.

Truth & Justice ends with some very useful reference materials. A sheet including the “normal” and “super” action resolution charts, a worksheet for creating characters, a nice character sheet, and a sheet for GMs to keep track of Story Hooks and NPCs. The production of the book on the whole is mostly fine, but it uses way too many fonts, including papyrus for quotes.

When I was talking about Risus I said that I’d want to use something more optimized for superhero play if I was going beyond a one-shot, and Truth & Justice is basically that game, at least in certain ways relating to cliches / Qualities. T&J has very simple, elegant, and easy to remember rules, as well as useful procedures / mechanics to help emulate the genre. For people who want something that runs extremely easy that occupies a middle ground between traditional and more narrative-y game design, Truth & Justice is a great option.

I do have some minor quibbles; the game doesn’t really have a great solution for power levels. Good [+2] Super Strength means being able to lift 1.5 tons, and Expert [+4] means being able to lift 75 tons. Chad Underkoffler says he’s more of a DC guy in the bibliography section . . . and yeah. It’s kind of obvious throughout much of the book that T&J isn’t really calibrated for more down-to-earth style Marvel heroes. It wouldn’t be particularly difficult to homebrew a different super scale table, but that’s not ideal, and it probably should’ve been included.

In order for the Story Hook mechanic to work, at least in the way it’s described, players also need to deliberately choose Qualities that will assist in that area. If a character doesn’t have something related to a relationship listed as a Quality, how can they get punched in the girlfriend? I don’t think most players would think to have a relationship as a Quality in PDQ, and I also don’t think it’s really an instance of munchkinism for a player to want to have all of their Qualities be skills.

If a player creates a story hook with their Computer Whiz Expert Quality, maybe it results in a villain hacking into their computer and sending their weird porn to their girlfriend, I dunno. Maybe I’m just not thinking about this creatively enough. The game does explicitly state that weaknesses, background info, origins, motivations, limitations, and vulnerabilities can spark Story Hooks, but those also aren’t necessarily Qualities or Powers, so it doesn’t work with the mechanic exactly.

Overall I think Truth & Justice is a very effective rules-lite supers game, especially if you want to play something that’s more Justice League than Avengers. At the same time, I don’t love it as much as I thought I was going to. I thought it was going to be my obvious favorite, but in the realm of team supers games Daring Comics and Marvel Heroic also feel very compelling to me. But, if I was GMing a Grant Morrison JLA-type game, it might be my go-to.

In my last piece I mentioned that Cam Banks and Michael S. Miller called Truth & Justice a great game. This game really does feel like something of a missing link in superhero RPG design, that probably isn’t discussed as often as it should be because it’s no longer available in PoD form, and also because older self-published games have a way of falling into obscurity.

Looking at the publication dates for all the games I’m discussing here, I feel confident saying that, in 2005, Truth & Justice was the best low-crunch supers game around. But now, and I really hate to say this . . . it might be a little dated. The game’s big advantage, and flaw, is that it uses intuitive action resolution mechanics and is easy to run, but you also are precluded from some of the innovations seen in FATE and Cortex Plus games. It’s not as noticeable in other PDQ games like Ninja Burger, I guess because ninja-themed food delivery doesn’t have as many points of comparison as the highly competitive superhero genre.

Additional Reading: 1

Sentinel Comics

Sentinel Comics is something of a spiritual successor to Marvel Heroic, if only because Cam Banks is one of its four credited designers. On Reddit I hear this game mentioned very frequently in recommendation threads, second only to the PbtA Masks.

The game uses the Cortex-y conceit of making a dice pool and extracting a number from it that isn’t necessarily the sum total of the entire pool. In Marvel Heroic and Smallville these kinds of rolls can be quite fluid, highly contextual, and narratively charged, but in Sentinel Comics players roll their character’s relevant Quality, Power, and Status dies together and take the middle result. If they don’t have a relevant Quality or Power they can use they roll a 1d4 in its place; 1d4 means “within normal human ability” for Powers, and “not particularly skilled” for Qualities.

In a game like Smallville I imagine that putting together a pool can sometimes be confusing if someone isn’t understanding how the game is meant to be played, but Sentinel’s core mechanic is a lot less contextual and a lot more traditional. I realize that, in many circles, that could be interpreted as me implicitly saying Sentinel’s mechanic is worse, and I’m not trying to imply that; having a system where it’s kind of impossible to not understand basic action resolution has its benefits, even if the trade-off is losing the potential richness of Smallville’s mechanics.

Let’s circle back around to Quality, Power, and Status. Qualities and Powers are basically analogous to Qualities and Powers in Truth & Justice; Powers are superpowers, and Qualities are skills that exist on a more “normal human” scale. Status is part of what makes Sentinel Comics unique on a mechanical level, because it ties into the “GYRO system”, which stands for Green, Yellow, Red, Out.

In Marvel Heroic characters had die values assigned to whether or not they were alone, with a buddy, or with a team, and that is similar to how the GYRO system works, broadly speaking. Characters have different die values depending on how much health they have, and this value doesn’t necessarily get smaller as they lose health; it can increase to signify they fight harder as they’re pushed to the edge.

Action scenes also move through stages, or “zones”, moving from Green into Red, and the state of a battle essentially overrides the health die, assuming the character hasn’t lost any health and the battle is in a Red stage. If the battle was in the Green stage and the character had Red health, they would still use their Red die; always the one closest to being Out.

The stages of a conflict and health don’t just affect the Status die, but also change which Abilities a character can use at a given moment; I guess in most other games Abilities would be most analogous to Stunts. Abilities frequently change the effect die in a roll from the middle to highest result, or allow characters to attack multiple enemies simultaneously.

If the heroes haven’t accomplished whatever it was they were trying to do before the final zone is finished, something bad happens, like the villain detonating his bomb. A common piece of GM advice is to add time limits to things, and this advice is mechanically built into Sentinel Comics.

You’ve probably realized by now that the GYRO system is designed to ramp-up intensity and create highly dramatic moments. The entire game seems to have a much more “on rails” feel and approach than other superhero games, where gameplay is either calibrated for action scenes or completely freeform talking scenes, and if I’m being honest I don’t really care for it in concept.

The book outlines montage scenes and social scenes, with the former basically being brief descriptions of what happens between action scenes, and the latter mostly being freeform talking with some overcome rolls if values are being challenged.

It’s support for non-combat stuff is pretty much just the Overcome/boost/hinder, which can be fine, but it’s mostly a combat engine. Not necessarily a problem. – Godfatherbrak

It really feels like there’s no room in Sentinel Comics for anything between these extremes. If I was GMing Truth & Justice, it’s very easy to imagine how someone playing as Spider-Man would covertly try to take photos for the Daily Bugle while doing investigation stuff. In Sentinel Comics, it would basically be a very brief montage moment where the outcome is basically just . . . described.

My players were frustrated by the lack of mechanics for non-action scenes. It’s not just minimal, the support is non-existent. In our last session, the players were investigating things, but their powers weren’t super relevant. They grew frustrated having to explain convoluted situations where they needed to invoke their powers just to get a non-d4 die felt limiting . . . Again, the fact that we want to have a scene with Daredevil and She-Hulk in a courthouse means we probably chose the wrong system, but that’s on us. There’s no Sentinels of the Multiverse courtroom drama. – CitizenKeen [1, 2]

I was talking about this game with a friend while reading the book, and they said it would’ve been interesting if dialogue scenes had more mechanical heft and if they used the scene tracker as well. For scenes where characters are trying to persuade one another, that definitely could’ve been very interesting, and I’m actually surprised it’s not in Sentinel Comics.

Anyways, let’s move onto random character generation. Much like Marvel Heroic, Sentinel Comics takes the approach of trying to funnel character creation in a way that is more likely to create a “logical” character. Players are explicitly allowed to just choose whichever options they like instead of rolling randomly, or even guesstimate a character that seems reasonably balanced on paper. I rolled randomly and created something that didn’t inspire me enough to create an alliterative name for it9.

This wasn’t anything wrong with the game’s character creation system, I just didn’t stop and start over when I should’ve. I don’t know why, but I convinced myself I’d be interested in transmutation this time. It’s like they say in Illinois, you can’t make “fetch” happen.

Health: 30

Green: d8 Yellow: d8 Red: d10

Green: 30-23 Yellow: 22-12 Red: 11-1

Background: Tragic

Personality: Sarcastic

Qualities: Investigation (d8), Imposing (d10), X (d8)

Principle:

-Defender

-Inner Demon

Power Source: Supernatural

Archetype: Elemental Manipulator

Strength (d10)

Weather (d10)

Transmutation (d10)

Vitality (d6)

Green Abilities:

-Backlash

-Energy Conversion

-Principle of the Inner Demon

-Principle of the Defender

Yellow Abilities:

-Area Healing

-Reach through Veil

-Live Dangerously

Red Abilities:

-Discern Weakness

-Charged Up Blast

After character creation the book has two different GM chapters. The first is called Moderating the Game, and the second is The Bullpen. The former is about running the game, while the latter is about creating adventures, villains, etc. These notes total up to a little over 100 pages, and so even if I think Sentinel Comics is something of an empty calories game I must concede that it provides a ton of guidance for a prospective GM.

Sentinel Comics is a well-designed book. The organization of writing is well done, and it has one of those things in the bottom corner that always tells you what section of the book you’re in relative to other sections. It isn’t a chore to read, and the number of visual aids and examples probably make this a very newcomer-friendly book. My only real complaint is that the book’s aesthetic can sometimes be a little overcooked in a way that’s kind of garish, and it also doesn’t entirely understand comicbook art.

The panel borders are frequently too thick and the line weights of the actual art are also sometimes too thick. The artwork is not necessarily bad a lot of the time, but it usually doesn’t match the conventions of the superhero genre. The example comics that show up from time-to-time look like Questionable Content, and there are a lot of Ben Day dots, which is maybe my least favorite comic art shorthand. All of this to say, the general presentation of the book is very functional and useful, but also I’m not in love with its aesthetic.

Overall, Sentinel Comics is a game that I don’t really have any interest in GMing or playing. It’s probably very easy to GM because of how rigid the gameplay is, and combat seems to have a level of tactical richness without being too complicated. But its entire philosophy of what happens during play feels incredibly limiting, and really highlights what old-school scenario design can bring to a game like Truth & Justice that a handful of big encounters connected by “montages” can’t.

Klaus of The Dungeon Newb’s Guide made a video breaking down how to play Sentinel Comics, which is a great resource if you want to play the game. The System Mastery guys have also discussed the game, and much like with Heroes Unlimited they’ve guested on the Character Creation Cast to make characters in the system.

When Part 3 goes live, I will put a hyperlink here. In Part 3 I will cover Aberrant, Astonishing Super Heroes, Cypher Claim the Sky, Marvel Universe, Codename: Spandex, and With Great Power. In the fourth and final part I will cover The Mighty Six, Four Color FAE, Aaron Allston’s Strike Force [which I realize is not a game in itself], Prowlers and Paragons, and Worlds in Peril. This list might change slightly.

If you enjoy Sabrina TVBand’s writing, you can read her personal blog, follow her on BlueSky and Letterboxd, view her itch.io page, and/or look at her Linktree.

- It is questionable to use an important term from a real-world religion in a superhero RPG, but I’m willing to cut Blacky [and anyone else making an MSH clone] some slack because it was the term used in the original game. But maybe we should try doing better moving forward. ↩︎

- Marvel Super Heroes also uses the term ranks, but the nature of how that system works doesn’t make its many ranks nearly as complicated. ↩︎

- I keep mentioning FATE, and it should be noted that FATE co-creator Rob Donoghue is credited as being one of the designers of Marvel Heroic. Fred Hicks, another FATE co-creator, contributed to the prior Leverage RPG, and so there’s a lot of FATE DNA in the Cortex Plus lineage. Cam Banks is even listed as a playtester in the earliest pre-Spirit of the Century versions of FATE. ↩︎

- This random character generator was included in the Civil War book. ↩︎

- It might sound like there isn’t much difference between an 8.5” x 11” and the standard comic trade size, but you might be surprised by how much comicbook retailers hate books that have non-standard sizes. ↩︎

- This is not an actual challenge. ↩︎

- At least Vox did, I’m just assuming S7S also does because I’ve taken a glance at the PDQ# document, PDQ# being the rules variant that S7S uses. ↩︎

- Truth & Justice does include a worksheet designed for creating characters, as well as an actual character sheet, but I didn’t feel like going into MediBang and writing on them for the purposes of this piece because I’ve been working on it for far too long; I think both sheets are well designed and there’s nothing wrong with them. ↩︎

- Much like with Truth & Justice this game does include great character sheets, but I didn’t use them. ↩︎

6 thoughts on “Rules-Lite Superhero RPGs Revisited: Part 2”