While roleplaying games can certainly allow players to explore certain things and work through some stuff, an important axiom to remember is that your GM is not your therapist. Therapy is a serious business, and you shouldn’t be unloading your psychiatric needs on someone who is not trained to handle it (or try taking on those needs yourself, if you’re the GM), for their good and your own. Unless, one supposes, they were your therapist first, and are now running a game for you as part of your usual appointment. Such is the purpose behind Role-Playing Games in Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide by Daniel Hand.

This is a weird one for me to be looking at, and the reason is right there in the article’s title. Simply put, I am not this book’s target audience. To pull a quote straight from the book,

“[This book] assumes that you are a trained, professional practitioner, qualified to work with clients on their mental health. If this isn’t you, I implore you to proceed with caution: you could cause real harm to the people you are trying to help.” [Pg. xxii]

So, while I have a lot of reasons to talk about why mental health is important, and can attest to therapy being a great thing, I Am Not A Therapist. There are going to be parts of this book that I can’t ever put into practice. So, why bother?

Well, the fact is that a large swathe of this book doesn’t have anything, directly, to do with therapy. And it’s those sections I can focus on and talk with some authority about.

See, the premise of this book is that it’s supposed to introduce practitioners to roleplaying games so that RPGs can be added to the practitioners’ toolkit for helping their patients. The thing is, that’s a tall order. Hand himself writes late in the book, “I appreciate that first impressions of this approach might be a little overwhelming.”

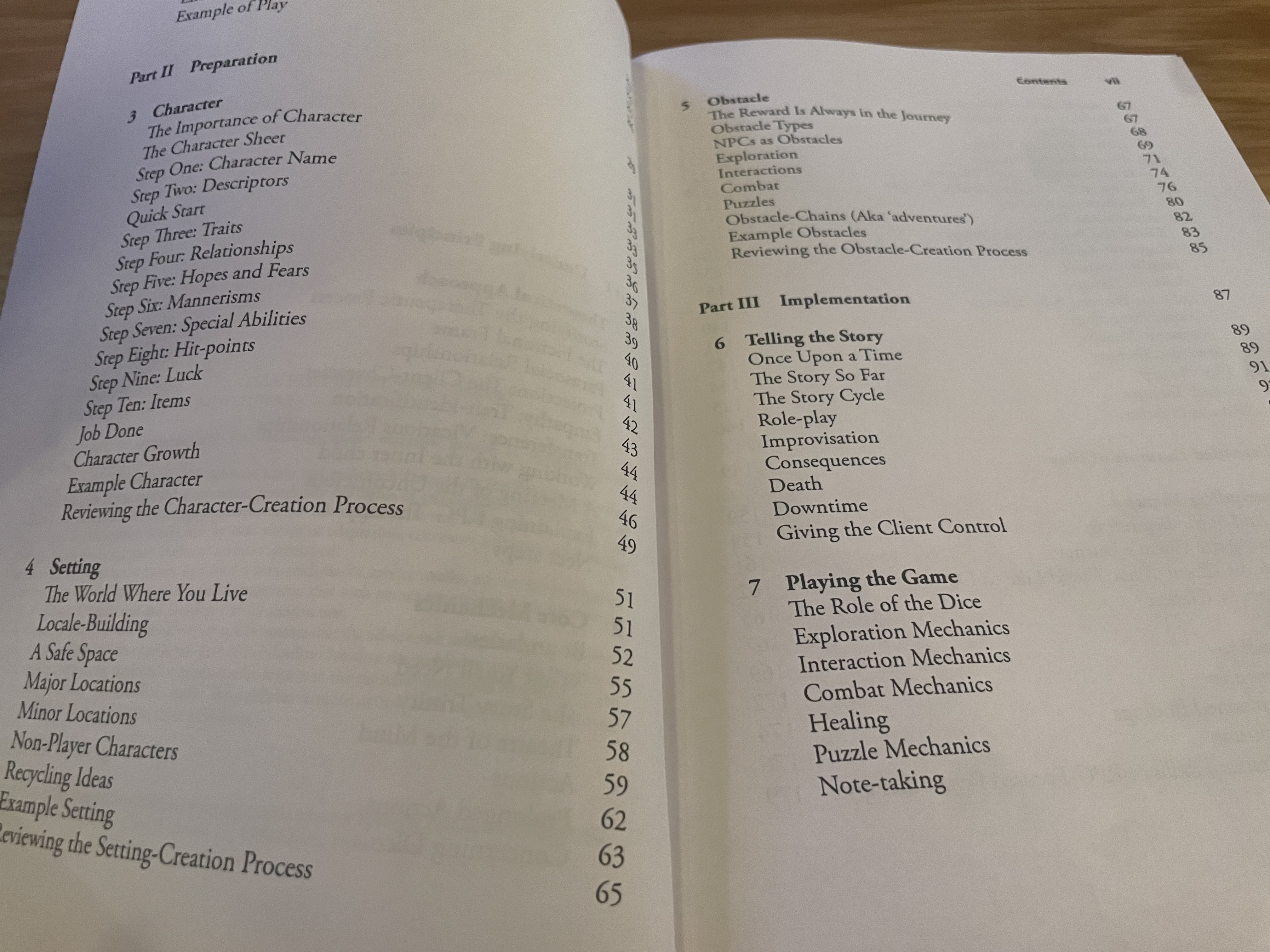

Out of the book’s ten chapters, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are entirely about roleplaying games and the act of running them, while chapter 9 is mostly taken up by an example of play. If you yanked out chapters 1, 8, and 10, along with any other wandering references to therapy, then you are still essentially left with Running Roleplaying Games 101. Let’s take a peek at the table of contents:

I wouldn’t say that the Guide is precisely all-encompassing, insofar as it doesn’t provide a full course on every topic; you’re not getting pages and pages of examples of Puzzle Mechanics, for instance. It does seem, however, all-encompassing when it comes to roleplaying games overall. There are few to zero aspects of roleplaying games (up to and including the practitioner getting out of the GM’s chair and giving it to their client) that aren’t covered to some degree, with advice on how to make them work and, yes, some examples here and there. Advice intended for the practitioner is often generally good advice; for instance, of those same puzzle mechanics the book advises a few layers of hints, from very vague to one-step removed, before stating:

“Of course, don’t rescue your client. If they show no interest in the puzzle or whatever lies beyond, don’t feel obligated to reward them for the work they didn’t do: this would come across as patronising, and also undermine the value of success in other areas. So let them walk away, and move on to a part of the adventure they’re eager to play. The aim here is to reward the attempt, not punish the failure.” [pg. 118]

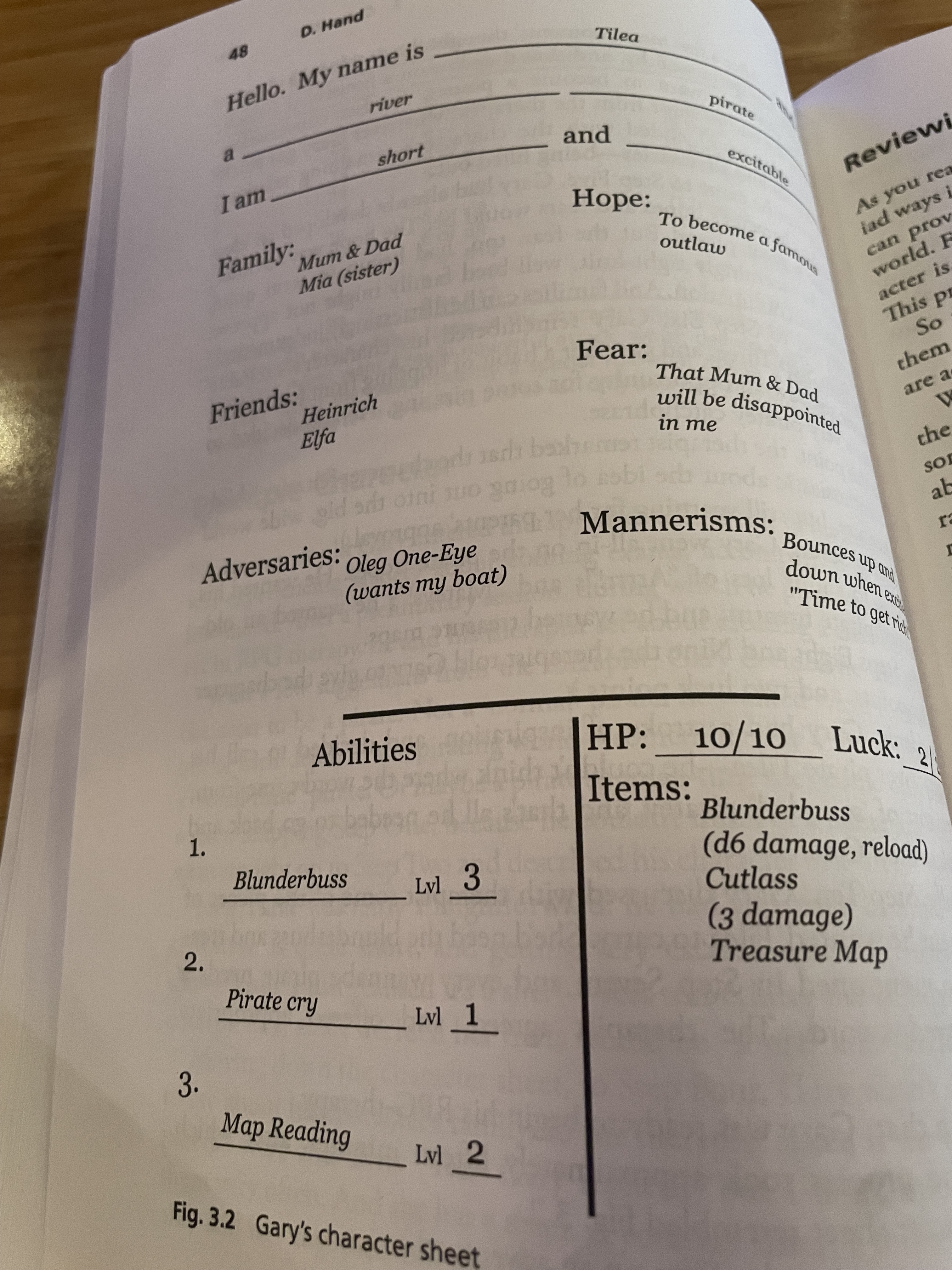

What’s particularly fascinating is that the Guide is actually, mechanically-speaking, a standalone product. This is not a D&D-therapy book; no game gets highlighted until the Resources section towards the end of the book, and D&D actually gets called out there as perhaps being too mechanically heavy for the purposes of RPG therapy. Instead, some simplified mechanics are presented for things like action resolution (introducing basic d6, 2d6, and d20 based mechanics), hit points, damage, and abilities (bonuses to rolls, and Luck points that get characters out of a jam). A sizeable chunk of the Guide’s character sheet focuses on things like the character’s relationships and their hopes and fears.

Now, as for those parts of the book that I can’t put into practice (I can’t just pretend they’re not there). They certainly seem well written. A large part of the premise seems to be that roleplaying games can essentially act as a buffer, a way to deal with things at a slight remove. The example of play, I think, might be one of the best in the business because it feels real, meaning awkward as hell. Patient Hayley grumbles, the GM/counselor has to scramble to keep their player from disengaging when things go badly for them, the therapist has to be running the game but also keeping an eye out for things that need to get addressed therapeutically-speaking. A somewhat over-reaction to bad dice provides an opening to explore getting frustrated and self-blaming for not managing to be ‘good enough’ at home, but only after continuing to play past the original problem and making sure not to push the patient too hard.

Chapter 8, Applying Your Modality, is among the most interesting as a layperson because it is addressing various approaches to therapy and how RPGs might interact with each of them, from Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy to Adlerian Therapy, from Attachment Theory to Group Therapy. Of Dialectical Behavior Therapy Hand writes:

“When it comes to DBT, with its history of helping individuals to accept and manage extreme, often overwhelming, emotions, RPG therapy offers that most important of learning tools: a friend to guide one through life’s turmoil. The incredible power of the relationship between a client and their character means that anything the character can do, the client can, too; if the character can be seen to work on themselves, the client can follow their example.” [Pg. 133]

For another example, of Systemic Therapy, ‘in which an individual is seen in the context of their wider pattern of relationships,” Hand proposes that-

“By reflecting upon ways in which the character may work to improve their situation by altering aspects of their system(s), the client becomes better able to plan and work towards making changes in their own. Furthermore, a practitioner is in an ideal position to role-play (or at least describe) various ways – both obvious and subtle – that the in-game system may change with the character’s behavior, thus modelling possible ways in which similar actions might influence the client’s situation.” [Pg 143]

So aside from trying to cover as many bases as possible on the RPG side, it certainly comes across as Hand trying to cover as many bases as possible on the therapy side as well.

While the Guide is trying to be the only thing you need (to get started, at least), there’s an impressive amount of research flexing going on; there are ten dense pages of further reading on (RPG) therapy theory in the Resources section. There is also a listen of further reading on the RPG side of things, and while Hand is quick to note that it’s not exhaustive it is extensive. Thirsty Sword Lesbians, The One Ring (Hand’s favorite), Quest, Cyberpunk RED, Masks, DIE, Twilight 2000, and Wanderhome are a fraction of the games mentioned and described in the book. If the Practitioner’s Guide is meant to be a gateway for said practitioner into the galaxy of RPGs, then Hand has provided enough destinations for it to be a friggin’ Stargate.

Role-Playing Games in Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide does an excellent job of explaining and introducing roleplaying games as an activity to someone whom it is assumed knows next to nothing about them. How a therapist then puts that activity into their practice, and what they think of Hand’s words on the matter as a fellow professional, well, that will be up to them. For the rest of us, though, it still provides a solid academic-grade example of how to introduce and and explain RPGs in general and running them in specific to someone. Also, as a fan of not just a or several RPGs but of the medium itself, it’s awesome to see someone taking an enthusiastic and professional stab at expanding what roleplaying games can do and mean for the people who play them.

There are both digital and physical versions of Role-Playing Games in Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide in several places such as Barnes & Noble. You can also check out Daniel Hand’s own site or Youtube channel for more content, both for the Practitioner’s Guide and other projects.

Did I mention that the Star Trek RPGs get mentioned in the Resources section?

Thanks so very much to Daniel Hand for swinging by the RPG Designer Meet & Greet at PAX Unplugged to talk about Role-Playing Games in Psycotherapy and give me a review copy to check out!

Oh my God, Seamus, that’s so kind of you. Thank you so much! It was an absolute privilege, having the chance to sit down and have a chat with you. I’ve already played Lost Among the Starlit Wreckage; just waiting to get my friends together for No Map, No Plan. Can’t wait to see you again, next PAX Unplugged 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for this resource and the comments. As someone who has suffered mental anxiety and depression, RPGs have been a source of light and resilience, a place to go and test approaches and build resolve. My usual role is actually as the ‘GM’ and that side of role-playing is also unexplored as to the potential to help gain some control over forces and events, but also to empathise and engage with the player characters and understand their perspectives and motivations. I have designed an RPG set in 2030, called ‘Sixth Horizon’. It is set in 2030, when the planet and natural and spiritual forces begin to fight back against the rampant degradation and alterations caused by humans. The game is not just about ‘saving the planet’, it is about saving ourselves … the focus is on persuasion, empathy and personality, working to get NPCs to join forces to join the ‘sunrise’ movement, working with neutral ‘navigators’ to thwart the exploitative and dark side of the ‘sunset’ faction. I am using it with nature conservation and humanitarian professionals to see themselves and their role in ways that help cope with the pressures of eco-grief, eco-anxiety and psycho-social pressures associated with environmental work at all levels. Play-testing has been brilliant and revealing. I am including reference to your book, Daniel, as I wish it to be used as a supportive resource for therapy as well. I include solo-rules as well, for those who could explore the potential to use RPGs in their own healing process, but always with the preference that this is a social exercise.

LikeLike