“Think about screenplays and films, or the final episode of a television show that you know will not be renewed. Think about saying goodbye to friends who are moving away. Think about the last day of summer vacation. Think about funerals. Think about the restaurant that closed all those years ago, and the noodles they used to serve. Think about the best birthday party you ever had. Think about putting off the last chapter of a book until tomorrow. Think about grief, and relief. Think about the end of a world. Think about the feeling of emerging from a movie theater into a dark parking lot, under the stars.” Longtime readers might recall I’ve written about saying goodbye to characters before, but that was largely in a ‘how to remember and treasure them’ way. The reasoning behind that article is, however, the same one that drew me to check out the subject of this one: the attachment to characters that we’ve created and a desire for closure as we leave them, and the snapshot of their lives that we played out, behind. This is a look at World Ending Game by Everest Pipkin.

A central concept to World Ending Game is the framework that the rest of its contents exists within: the language (and camera angles) of film. Players are labeled as the Director, the Leading Player, and the Supporting Players. If the campaign that World Ending Game is bringing to a close has a GM, they’re a good choice for the Director since they’ve had such a similar role up to this point. If there wasn’t a GM, or if the group prefers, the role of Director could shift from player to player.

The Leading Player is a shifting role as well, although unlike the Director it is always a shifting role. The Leading Player is the one who chooses which Ending to play through, can often be thought of as the protagonist or focus character of said game, and then cedes the role for a new player to take and choose in turn.

The Supporting Players in a scene are everyone else who gets involved in a specific game chosen by the Leading Player – for some games there might not be any, for others the Supporting Player might be the deuteragonist, and for some everyone will be joining the cast as it were.

The Director is responsible for kicking things off and wrapping things up, but the core part of their experience is that they control Camera Direction. At any point during any game or scene therein, the Director can interject with a Camera Direction, altering how the audience views the scene. This could be a direction to Change Angle or Change Zoom, to Change Subject or make a bold aesthetic choice in line with your Artistic Vision, to Record a Voiceover or make a Hard Cut, or even to Ask a Question or Suggest a Change of the players.

More film language comes in with the fact that the group is encouraged to make edits or cuts, altering what they’ve covered or leaving it, well, on the cutting room floor if it no longer fits the send-off the group is constructing. Dice don’t come up much in the game, but when they do they are at the mercy of the group, not the other way around; if the random number gods gave you a conclusion or material that isn’t satisfying, put them back to work until they do.

The Safety Mechanics section builds off this yet again, advising that a film rating is given to the overall game, reminding the reader about the ability to cut content, and providing guidelines for keeping things off screen or out of the script entirely (lines and veils).

Before beginning play proper, everyone at the table covers Up Till Now – a little questionnaire of which there are two versions, one for the Director and one for all of the other Players. The Director is answering questions about non-player characters (which one felt most like you, which one wants rest, which one is tangled in something bigger than they know, etc.) and the world (what was set right, what was made wrong, what was never shown that you want to be seen). The Players are of course answering questions about their characters and their experiences during the campaign – what moment will you return to when thinking of the game, what does your character most regret, what does a happy ending look like and do they think they deserve it, what is unresolved, etc. Everyone is also picking out a number of songs, or at least describing what kind of songs, that best fit the strongest moments and characters in the campaign. If possible, a playlist gets created or links are gathered – some games expressly call for music to be played, but a song can always be made part of a game at the discretion of, you guessed it, the Director.

Finally there are a number of other little notes and alternate rules in World Ending Game to cater things to your exact circumstances and preferences. Advice for playing online, more involved rules for getting music involved, different ways to handle the Director (or the GM-less version thereof), and a Season Finale rule that consists of one of my favorite pieces of roleplaying advice that just happens to be popping up a lot lately: play these Endings like they’re a stolen car.

Saying Goodbye

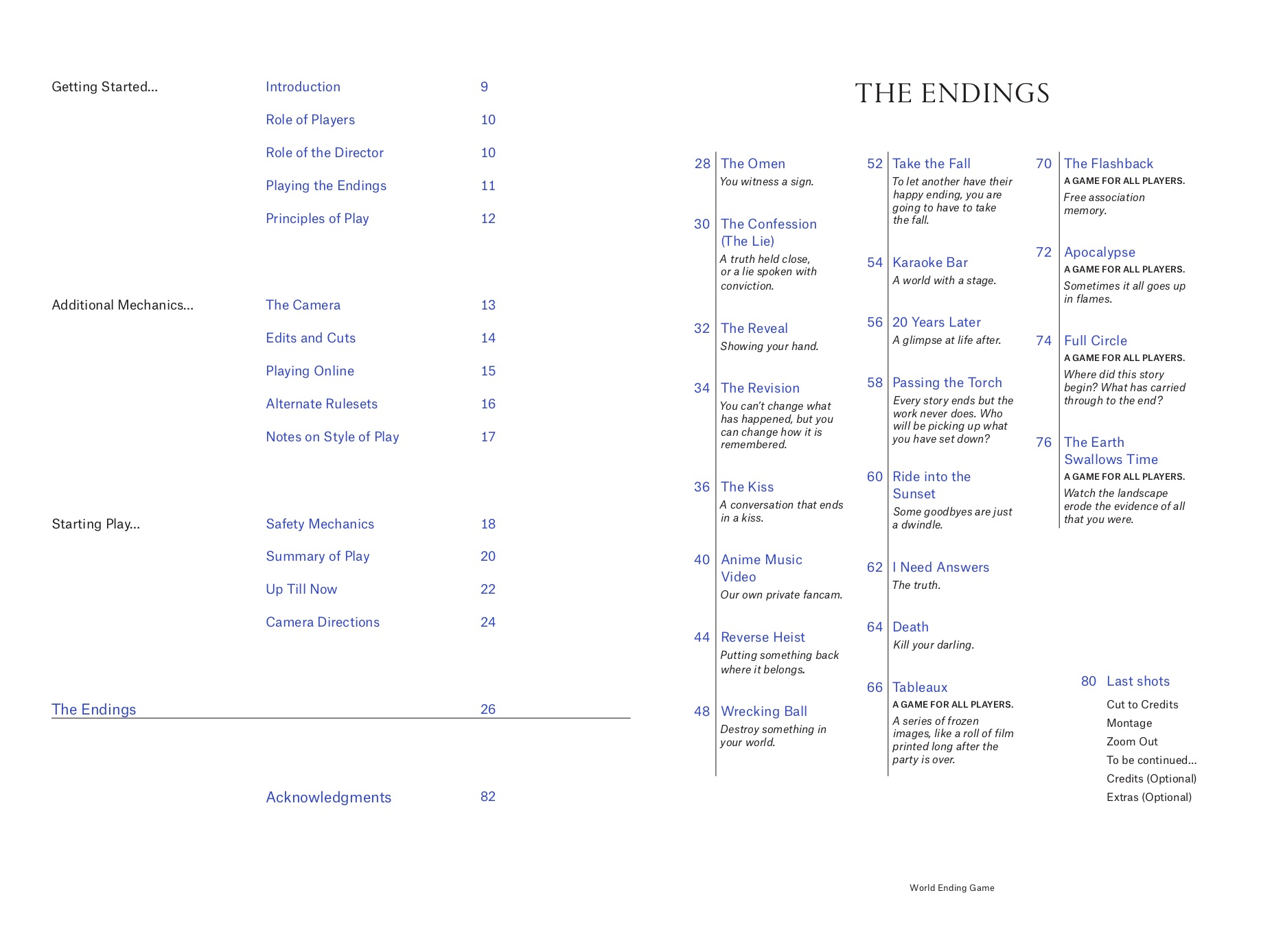

So, now we get to the heart of things – the 20 small games, the Endings, that you’ll be picking and choosing from to play through. The Table of Contents is freely available so you can figure out very easily, if in broad strokes, what you’ll be getting into without ever seeing another page.

The most surprising thing about World Ending Game is that it gives a strong sense of being a multi-author anthology when that’s not the case. While there are plenty of people involved, and we’ll address how later, all of the actual design work is done by Pipkin themselves. There are single page games, multi-page games, games that are a table of options to interpret, games that need dice, games that don’t need dice, games that are extremely loose, games that follow a script, games that give you options, and games that ask you questions. The Director chooses and is the Leading Player for the first game you play, and then the player to their right becomes the Leading Player and chooses another Ending. This proceeds, functionally, for as long as the group feels it needs to, although you’ll want everyone to be the Leading Player at least once and in the end the Director has final say over when it’s time to bring things to a close.

So, let’s take a look at a few examples.

The Reveal is a game about, well, revealing something secret to the audience, meaning the rest of the players (as opposed to an earlier game in the book, The Confession, wherein it’s an internal reveal that the play group has known about out of character). It’s highlighted as a good choice for the Director’s first scene, although doesn’t lock anyone else out of it – everyone has secrets, after all.

A single page and very freeform, the Leading Player is simply directed to show a truth about the world that has been taking place ‘off-screen’. “Describe what the camera sees, as it frames an image away from or hidden behind past actions.” Perhaps a previously unknown explanation for a why a character acted the way they did in a given moment, what happened at home while the heroes were off doing their thing, or what strings were being pulled in the shadows,

The Kiss is, unsurprisingly, “a conversation that ends with a kiss.” Equally unsurprising given its intimate nature, it’s one where you’re reminded to review your table’s safety tools. The Leading Player picks another player character or an NPC to share the scene with; if the other character’s controlling player refuses, directions state to pick another game to play, rather than trying to choose another character.

What’s interesting about this one is that the two characters spend the start of the game taking turns, but the questions asked are about describing the other character’s actions. For instance, the Leading Player’s character arrives first to the meeting point, and is asked how the Supporting Player’s character feels about seeing you waiting for them to arrive. The next bit is about the SP’s character seeing the LP’s character first, asking how you find them and what they were doing to pass the time before you arrive.

Eventually this format ends, and the LP is prompted to ask a question (will you come with, will you forgive me, etc.), the SP to answer, and you can continue the game in freeplay… until SP chooses to be kissed and picks what kind kiss they receive (halted before it landed, on the hand, on the lips, a smile that wanted to be more, etc.), LP picks a descriptor for the kiss, and the scene ends.

Death covers exactly what you think it does, giving the Leading Player power over how their character pushes off this mortal coil. After a quick review of yon safety mechanics, the Leading Player decides what exactly is putting the final period on the book of their life. Supporting Players can be witnesses, or might even be controlling the character who does the deed if that’s an acceptable choice for all parties.

The Leading Player frames the scene, establishing where the character is in the moments leading up to their death: a hospital bed, a dream, an adventure, a fight, simply walking down the street, etc. Then they narrate or roleplay out the last few minutes of their life, and may decide to know death is coming or be caught be surprise. The Supporting Players dictate the last thing they each say to the Leading Player’s character before they go, with the Director interjecting as appropiate with things like Camera Directions and narration.

Finally, the Leading Player speaks their last words or takes their last action, and makes peace with goodbye.

Passing the Torch might very well involve a death – the art has one arrow-riddled character, surrounded by fallen warriors, clutching a sword by the blade and holding it out to another – but the crux of it is that the Leading Player is giving something away. This could be ‘an object, a weapon, a secret, a story, an impulse, or a mission,’ but in any case this isn’t a case of lending, it’s out of your hands forever. First, the Leading Player chooses another player or non-player character – if they refuse, the LP can choose another character or choose another game. Next, they choose exactly what it is they’re giving up – if the original game is one with character sheets and the ‘torch’ is written down, they cross it out.

Next, establish exactly how the torch is passed. Is it spoken of, or wrapped up in an activity, or found some time after you hide it away, or something they’re begged to take on? Is it something that comes with obligations to follow your own path?

An interesting dial on this one is that you’re outright told that you can choose to play this scene out or to simply describe its outcome; either way, you should make sure to describe both how your character feels having given something up, and how the inheritor feels having taken it on.

Tableaux is “a series of frozen images, like a roll of film printed long after the party is over.” The Leading Player picks any one of a number of provided prompts, addresses it, and then passes the book/spotlight to the player to their right. Just like the players, the prompts are arranged in a circle in a two page spread, and each subsequent player plays the next prompt in order, so where the Leading Player chooses to start can have a pretty big effect – particularly since you play until you complete the circle of prompts, or under the table decides Tableaux is finished.

Prompts start with such statements as ‘You are cooking a meal,’ ‘you are laughing with loved ones,’ and ‘you are fixing something’, and interrogates the statement from there. Is anyone waiting to eat what you make? What are you worried about in the back of your mind? How was it damaged?

For a final, more visual example, check out Karaoke Bar:

Style

You’ve seen some glimpses of it while reading this, but the production values and care of design choices for World Ending Game cannot be overstated.

First you could judge the book by its cover, and what a cover it is, with shiny gold text, stars in the sky, and what looks like a meteor plummeting to the earth. Physically, the cover and the pages within are both a fair bit sturdier than you’re probably used to with products of this size.

Then, there’s the interior design.

Every single game has at least one full page of art, and each one is from a different artist (no AI nonsense in this house, that’s for sure). Each game outside of the opening rules and explanations also has a unique layout, each designed to complement the accompanying art. A list of typefaces used in the book is included in the Acknowledgements at the end, and it’s a brick of text.

Nothing about how World Ending Game is designed as a visual experience is random, left to chance, or for that matter in line with the rest of the book. The layout complements the art, and both are tailored to fit with the subject matter and vibe of the Ending they have been created for.

Opinions and Conclusions

Practical mileage will of course always vary with this kind of product, even from game to game within this book. On a personal use level I’m of slightly mixed feelings about World Ending Game. An epilogue session wrapping up a campaign is not a foreign concept for… almost all of the groups I’ve played with or run for, really. At no point did those groups need the structures and framework that Pipkin has provided here, and at some points we pretty much came to the same destination but via our own path. I think most strongly of a Masks campaign that had a scene between the Reformed, the Doomed, and the Protégé that was similar to but would’ve strained against the structure of The Kiss.

At times I found myself wishing there was some more general campaign-ending advice, but as I read the book over again and thought about it some more (and as is typical for these sorts of reviews) I found several advocates infernal.

First, it just so happened that when I was reading World Ending Game the discourse de la semaine was, in part, about fruitful voids. Can you have a completely fulfilling epilogue or ending session of a campaign with no mechanical framework or support? Yes, absolutely. It is still a void in many, I think I can comfortably say almost all, roleplaying games. Even games that take the Where Are They Now? tack don’t spend a great breadth of words or rules on wrapping things up.

For a given group, that void may be a fruitful one… bot for another it may be just a truly empty space, and for groups like that World Ending Game seeks to fill things in. A game’s rules can often tell you what the game cares about, and for roleplayers who both care about the epilogue and are looking for a system that shares that care, World Ending Game fits the bill.

Second, how to end a World Ending Game actually does cover a bit of the completely freeform stuff. The Last Shots section of the book is for bringing things to a close, and offers four unique Camera Directions for the Director to choose from: a (hard) cut to credits, a montage, a to be continued, and a zoom out. The first three include a scene or a series of shots, completely up to the Director, to close things out. Furthermore, the optional Credits and Extra involve input from everyone, and are actually pretty fun frameworks meant to mimic talking with friends in the movie theatre while the credits run and the in-universe stingers at the end.

I still would have liked some generic ‘how to say goodbye to a campaign’ advice, but on the other side of the coin the entire book is made up of examples that may serve that purpose. You’ve essentially got a bunch of ideas for an epilogue of your own making, if you tear out or tweak the already-sparse mechanical guts of the Endings.

Finally, the World Ending Game ticks all the boxes for being a genuine work of art. Some of that, yes, is wrapped up in how much of the physical product is made up of and designed to look like art. The thing about art is that it is made to evoke an emotional response, to make you feel. Every game within World Ending Game is tailored to do so in a specific way, letting you draw out a variety of such responses to your liking as the group picks and chooses both the games to play and what to do with them.

Also, it must be said, unlike a lot of ‘system agnostic’ game add-ons, World Ending Game is way universally useful because it’s as free about genre conventions as it is about rulebooks. No heavy lean towards fantasy here!

—

You can get a digital only copy of World Ending Game for $15 at itch.io (complete with plain text versions in both English and Spanish), and you can also get the physical version there, at Deernicorn Distro, or at Indie Press Revolution (where I got mine at PAX East ‘24) for $40 plus shipping. For sheer number of pages (~80) that price may seem steep, and I’ll admit it had me hesitating for a bit at first… but I’ll agree with the IPR blurb, this is a game you want to be able to hold in your hand if at all possible. That being said, it’s important to note that on their own site Pipkin makes a point to say that those who are suffering financial hardship should reach out for a free PDF copy, no questions asked.

Gather your things, say what you need to say, and walk away from the story you have been telling with confidence and pride.

2 thoughts on “World Ending Game – Saying Goodbye With Style”